Last May, I clicked on the horoscopes of Galactic Rabbit, aka Gala Mukomolova. I readied myself. I was in a fragile state, and Gala — who is a real-life friend — often writes such insightful horoscopes that I sometimes cry after reading them.

The night before I had drunk too much whiskey and tried to dance the semester away at an East Village club with several twenty-something queer friends. The after-effects of my debauchery were intense. I hadn’t managed to leave my apartment and it was late into the afternoon. My head throbbed and I decided in a hung over, self-pitying way that while I was capable of intense outbursts of unbridled fun and wildness, I was forever to be punished with solitude and deep bouts of loneliness.

I read Gala’s opening letter to readers, which included the heart-busting sentence, “There are those of us who have always felt alone in the world, intrepid, aliens in every community we find ourselves in,” and then scrolled down to the entry for Gemini. In it, Gala writes about a rare phone call from her brother, his offer to help her if she needs money, and the relief of this gesture:

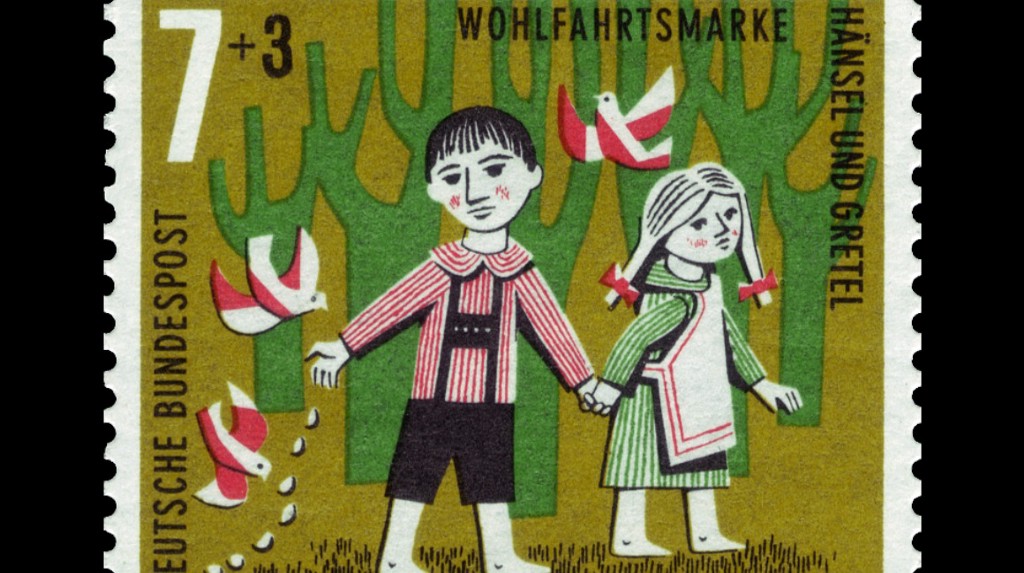

Isn’t this what all lost children do? Find a way to survive. Partner up. Hunker down. Escape. Gala’s story about her brother spoke to me because like many children, who emerged from less-than-ideal childhoods, I have long thought of my brother as the Hansel to my Gretel. Somehow long ago, we’d made a pact in the woods to protect each other. It was a fairy tale we told ourselves.

My brother recently sent me a text that he had the potential in his new business to do quite well, and that if that happened, he would take care of me. I didn’t press it. We text occasionally and talk on the phone hardly ever. When we see each other, I feel close to him, but we have long chunks of time when we don’t communicate at all.

Part of me didn’t believe him, and part of me felt stunned by the love of it. And yet I’ve learned to expect no help from anyone, and to believe only in myself. Why is my brother still offering to take care of me? Does my life look that precarious? Is this what adult children do? Is there something inherently worrisome about me as a single, divorced, American mom? I wondered.

Maybe I didn’t believe him because I’ve lost the ability to believe that anyone I know in this country can succeed in that wild, hopeful, “American Dream,” middle-class way. If 47% of Americans (and I’m one of them) would have a hard time coming up with $400 in an emergency, and our government continues to care so little for this reality, how could I believe in a windfall, familial or otherwise?

And yet like many Americans, I suspect I am tethered to two conflicting ideas. Sometimes I think if I scrimp and save enough I just might make the whole bootstraps-bullshit American Dream a reality. Other times, I wallow in my own financial failures. Why do I still live paycheck to paycheck? What is wrong with me that I have so much debt?

And I’m honestly confused about how families help each other; aside from splitting the cost of my undergraduate state school education in the early ’90s, my parents have never given me any money. I have friends who have used family money for apartment down payments or college tuition for their children or who are expecting inheritances when their parents pass away. But then I have other friends, like me, who go it alone.

I know people who are broke, but if they had any extra money would give it to their kids or friends in a heartbeat. I went on a bad date with a man who’d been unemployed for five years, living with his sister, and paying no rent. When I asked him if he ever felt like he should contribute, he waved me off, “It’s family. This is what we do.”

I ran away so fast from that date that I fell into a snowbank. I couldn’t see his arrangement with his sister as anything other than a grift. I feared he was just looking for another woman to feed and house him. Still, I understand that in the absence of any substantial government intervention — a living minimum wage, national subsidized child care, and a real commitment to affordable housing — our nebulous and complicated relationships with family members are what’s left.

As I wrote this essay, I scrolled through my friends’ Instagram feeds. It was Pride in NYC, and I was filled with a weeping love for the queer friends that have held me, loved me, and become my family. I take in the shirtless photos and signs that read “Gays Against Guns: GAG!” and “Yo Soy Pulse!”

From my window I could hear the roars of joy from the parade. I have a stupid, stubborn hope that love will win, that the world is changing for the better, and that we are in the last ugly, violent, bloody throes of rape culture, patriarchy, and a racist system that is dying, but so slowly that it almost doesn’t feel like a death at all.

All is not lost, I keep telling myself. There are new maps and new families and those who are lost will find a way to catch up.

![]()

Lost Boy

Once my brother and I actually got lost in the woods. We were at Alleghany State Park for my father’s annual office picnic. I would later appreciate the event for its drunken contours, but at the time it just seemed like a really good party for kids. Unlimited cans of grape soda! Pringles poured out of the canister into giant bowls! Let’s dig a hole to China on the beach! One year my father puked into our plastic beach bucket as my mother drove the car home with us in the front seat with her. Another year, my mother cried on the sidewalk outside of our house, and my father had to beg her to come inside.

There was a path into the woods from the picnic site. We took it. There were other kids too. Chatter. Bravado. A girl my age named Beth whose father owned a boat. She had a beautiful Dorothy Hamill haircut that worked because her hair was thick, not fine like mine. And there was a new young stepmom who wore high-heeled sandals. Her little sister Amy was cute and petulant. I wanted to impress them and got caught up in the stories we each told about the stupidity of sixth grade.

It was late in the day and I was walking, so this was definitely post-recovery, after a doctor in Toronto diagnosed my rare neurological condition and gave me a magical pill that changed my life and made it possible for me to walk again. Maybe I was high on that freedom. I could walk anywhere! Maybe I remembered the little patch of woods between houses in our old neighborhood where a boy who was two years older and I stripped naked and pressed our bodies together. Front side. Back side. Electricity.

Maybe I understood at that early moment in the woods with that boy that I was a witch or that I’d pretty much do anything for sex because it meant pleasure and escape. Probably not. Everything I did then was underground, unconscious, and subterranean. Motives were not something I could identify accurately in myself until my late thirties.

“My dad will be mad,” Beth said, speaking the universal ’80s code for spanking and grounding. They wanted to go back, so we waved good-bye to their haltered, sunburned shoulder blades and kept walking. Maybe we were running away. Maybe we were on an adventure. Maybe my brother was excited that I could finally walk somewhere with him. He’d been playing in the woods next to a new housing development up the road from our house for the last year and coming home with small snakes, which he kept in shoeboxes with holes in them until they escaped. Maybe we’d already seen E.T. and Goonies and we believed in the power of children to change the narrative of adult lives. Our parents didn’t seem to like each other very much. Maybe we wanted to walk away from that sad reality. Maybe we were just having fun.

Somehow we got turned around. We wound up on a different path by trees we didn’t recognize. The woods got thicker and the path more narrow. Eventually, the path opened up onto what we thought was the office picnic, but instead was an empty ranger’s station and a road with no cars on it. The scene was eerily quiet, like a set from The Twilight Zone. There was no park ranger or any other hikers, and definitely no other kids. The sun was starting to set. We chose another path, and then another, but they all looked unfamiliar and wrong. We were not calm kids. My brother regularly entertained fears of getting kidnapped by a man in a nondescript white van. I had never recovered from watching Poltergeist, and believed at any moment that a tree could swallow me whole.

We followed one of the paths back toward the abandoned Ranger station. We looked closely at the map pinned to the wall, but we couldn’t read it. We didn’t know where we’d been, and the map didn’t look anything like the ones my parents kept crumple-folded under the passenger seat of our Toyota Corolla. It had blue lines on it to indicate topography, but no “x” to indicate where we stood.

“We have to just walk,” I said.

“But which way?” My brother looked more panicked than I’d ever seen him.

“If we just get on a path and stick with it, we’ll find them,” I lied, and started to lead us down the path that felt right to me.

My brother fell behind me on the path, silently crying. It was almost dark. “We can’t be alone in the woods at night,” he sobbed.

“Don’t cry,” I maybe said.

He rushed forward and hugged me, clung to me really, and stammered, “You have to help us. You have to figure it out. You’re the oldest. It’s your job.”

I hugged him back and patted his back. I realized that for all of his farting bravado in our family room, his figure-four leg locks, and his ability to dribble around all of the soccer players in his league, he was still only 9. Something in me clicked into place, and I knew that no matter how afraid I was, I had to hide it from him, and get us back to the picnic. I was the oldest. He was too scared to think straight. I had to find our way.

Somehow I picked the right path. It’s possible that all of the paths led to the picnic area and we just needed to commit to one, and I’d helped us do that. I started to recognize certain trees. I kept us moving, and I refused to cry.

It was dark when we got back to the picnic site and all of the parents were packing up. It never occurred to us that any of them would come looking for us, and they didn’t.

“Beth said you were just behind her,” my mother said as she folded our lawn chairs into the hatchback. “So we’ve just been waiting.”

We drove home in silence. Our parents were mad, but they couldn’t grasp or we couldn’t speak to the enormity of what we’d just experienced. We were lost in the woods. We thought it was forever, but we found our way back. We were Hansel and Gretel without the breadcrumbs. What scared me most of all was that our parents didn’t even really get it. I saw then that they couldn’t protect us forever, and that we were capable of getting hopelessly lost, while they were distracted or fighting or having fun.

I am your little mother. Take my hand, and I’ll show you the way. I’m clever. I know the witch. I am the moon. I can churn butter and sew a dress. I’m plump and dimpled, though there are hard lines across my body. Let’s call them Chin, Nose, and Face. Don’t cross them. I am the map. The topography’s inside of me. Let’s call it blood. I am the lost twin. I’m Gemini and I’m always looking for you and you and you and you. I was made for pleasure. I was made for work. I can find a needle in a haystack and any boy, in any woods, any where. Except for that one little boy, who got away.

![]()

Re-Birth

My pregnancy began as a twin pregnancy. We lost the other baby at the end of the fourth month. We’d already named him and the loss terrified and saddened me in a way I’d never experienced before. Still, I didn’t allow myself to grieve. No one knew why that baby died, and the rest of the pregnancy was high risk. I felt I needed to focus on the other baby, and do everything I could to get her out of me alive.

Recently, because she is 7 now and we were talking about how she was born, I decided to tell my daughter about her twin. I wanted her to know, but I didn’t want to tell her too soon. I explained it in as matter of fact way as I could. You were once a twin. There was another baby, but he died before you were born.

In the way that all major parenting events don’t happen the way you thought they would, my daughter’s response surprised me.

First, she asked, “Why didn’t you tell me sooner?” which was a perfectly good question.

“I wanted you to be old enough to understand,” I managed, and then added, “And also I was sad for a long time about it and it took me a while.”

Then, maybe because she is a Leo, she said, “It’s okay Mama, I like being an only child.”

“Yeah, it’s pretty nice, isn’t it?” I said. It was a Saturday morning. We were cuddling in bed.

“What was his name?”

“Sal.”

“What kind of name is that?”

“It’s from a book Daddy loved and also that was his grandfather’s name.”

“You like old names.”

“Yeah, we do.”

And then she suggested we pretend she was being born again and I went with it because what else was going on that Saturday morning? She play acted a baby’s high-pitched cries and I pretended to push her out again under the quilt and it was silly and healing in a way I couldn’t have ever imagined.

Since then, she has told close friends about her lost twin. These sweet girls have listened intently and one even added a story about the baby her mother lost before she was born. In my daughter’s later re-enactments, her twin was born with her and then died. She treats this story as her own, mutable and changing depending on each performance. I have not corrected the details. We can return to those later. It’s her story. Perhaps not even mine to write about. That was her twin, her brother, her lost boy. Gone long ago into the cosmos, where desire and longing and mourning swirl around in a galactic stew. If this galaxy could speak to us, it might say, Who are you looking for? What have you lost? Where are you going?

Recently, while walking in a cemetery with her dad, she asked, “Do you think he’s here?” Around that same time, she told us that she doesn’t like it when people say she’s lucky to be an only child. “Because I might have wanted a brother,” she said to us as she bounced on top of one of the couch cushions.

I suspect that her feelings about her lost twin will change and change again. I can’t know what it’s like for her to have been a twin, and to have lost a future brother before he was born. Did she feel him swimming next to her? Were they communicating inside the womb? Did she know when his heart stopped beating? These are cosmic questions. Hard to ask and unanswerable.

I suppose in talking to her and in writing about it, I’ve accepted that loss, grieved for that baby that never quite was, and still he was a little boy who got away, the one I couldn’t save. I was not to be his little mother. Nor she.

![]()

Star Light

When I was 17, I visited a psychic in the small town of Lily Dale, New York, the spiritualist capital of the world and just a half hour away from my hometown. I went to the same psychic my father saw once a year. I’m not sure why he went — he’s a hardcore atheist and scoffs at most anything that’s not science-based, but he liked her and said she was the real deal. I believe her name was Anna May Dodd, though my Googling can’t confirm this, and she’s long since passed away. As a goth/punk teenager, my friends and I were drawn to Lily Dale though we often did no more than wander the grounds and marvel at the small tombstones in the pet cemetery.

She met me on her porch, and we stayed there for the duration of the reading. She told me nothing about my future, but she described my life to me in a way that felt miraculous. She understood the dynamics of my falling-apart family and she told me that I would make it out. She described my parents to a T, and when she got to my brother she paused to wave to a neighbor on the barely paved street, and then continued.

“You can’t forget about him when you go. He needs you. You have to take care of him.”

I nodded, struck by the urgency of her tone.

“Is something going to happen?” I asked.

She shook her head no. “I have a brother too,” she offered and moved onto something else. I left her porch that day stunned and grateful because I felt profoundly seen, visible somehow in this 70-year-old woman’s light. I felt similarly when I met my current therapist four years ago.

Was that psychic right? Did my brother need my protection? Who was watching out for me? I still feel that I failed my brother because I left our small shitty town and went to college in the midst of my parents’ messy and bitter divorce. Three years later, he left for school too. Perhaps I’ve cast a psychic net of care and love around him. I hope so, but I really can’t say for sure. We’re adults now. We have a close, but careful relationship. There’s so much I want to say to him, but I’m not brave enough yet to do it.

Still, I no longer feel like we’re living in the woods. We’re not those lost children anymore. In fact, when I text him about his memory of that day, he doesn’t remember any of the details. Was it an office picnic? Were there other kids involved? he texts me back, and I’m left to wonder why my own memory is so intense and cinematic. Is it because I write personal essays? Does my brain excel at turning images into stories? My brother is often the only fact checker I have, and unlike me, he lives very much in the present.

I am not your little mother, though I can be very tender. If she calls me Mama, I do what she wants. I’m weak that way. You’re such a smother mother, he once joked. You’re drawn to lost boys and Peter Pans. You don’t need a map anymore. You know the way. The path is lit up. There are fireflies or small lanterns. X marks the spot. Keep walking. Keep moving. Look up at the stars. The galaxy sees you. Ask your questions. Wait for answers in the stars.