If we want to progress forward today, we must start from a place of shared resistance.

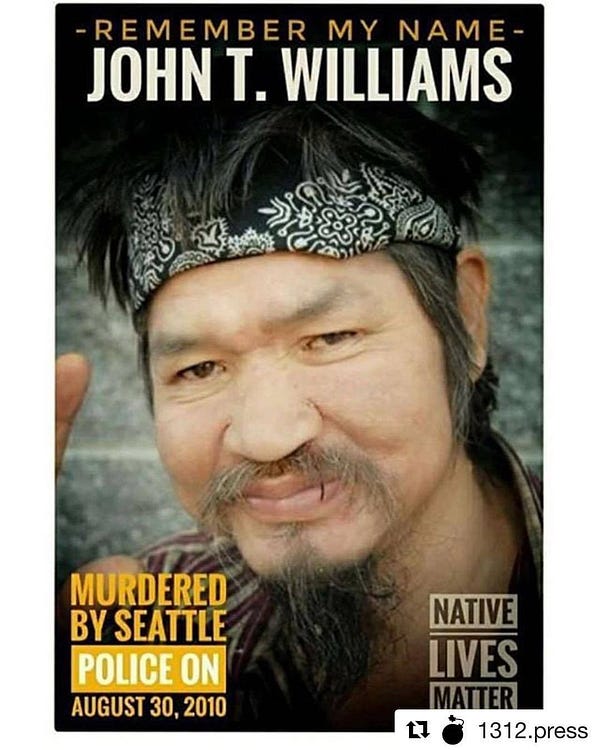

More than seven years ago, John T. Williams, a Native woodcarver, was killed — some would say murdered — by Seattle Police. The police killing was met with great protest by the Native community and allies, ultimately helping to spur a Department of Justice investigation that resulted in the Seattle Police Department being put under consent decree for excessive use of force and possibly racially disparate policing.

Earlier this year, when a photo was published on Facebook in remembrance of Williams with the hashtag #NativeLivesMatter, an online debate ensued. Native people, some commenters argued, are co-opting “Black Lives Matter” by saying “Native Lives Matter.”

Co-optation is — it should go without saying — a very real and serious issue. But in this case, I think we are missing the point. “Native Lives Matter” is not co-optation; it’s a necessary reflection of solidarity. In fact, I’d argue that it’s imperative for Black and Native peoples to see how our past, present, and future are inextricably tied together, especially in light of the most recent police killing of 14-year-old Jason Pero.

It’s not something Americans like to talk about, but the inception of the U.S. was largely incumbent upon two forces — the genocide of Native peoples and the enslavement of Black peoples from Africa.

The United States was built upon genocide, stolen land, and stolen peoples — and this difficult, unconfronted truth continues to inflict harm on both Native and Black peoples today, through state-sanctioned violence, police terrorism, and mass incarceration.

So why do we not always see our fight against white supremacy as a shared one? In part, this has been by design. Early slave states were dependent on separating and building animosity between Black peoples and indigenous peoples because our shared resistance was so strong. For example, Seminole Tribes and many black peoples of African descent lived in close relationship with each other in Spanish Florida, where slavery had been abolished in 1693. As a result, many escaped slaves retreated to the area and became known as Black Seminoles. Throughout the first Seminole War, Black and Native Seminoles fought together, but as Indian Removal continued and the southern slave states colonized more land, a divide would be brought between Black and Native peoples. This divide would ultimately weaken our resistance — forcing the relocation of most Seminole tribes and the fleeing of Black peoples to free states and nations.

So why do we not always see our fight against white supremacy as a shared one? In part, this has been by design. Early slave states were dependent on separating and building animosity between Black peoples and indigenous peoples because our shared resistance was so strong. For example, Seminole Tribes and many black peoples of African descent lived in close relationship with each other in Spanish Florida, where slavery had been abolished in 1693. As a result, many escaped slaves retreated to the area and became known as Black Seminoles. Throughout the first Seminole War, Black and Native Seminoles fought together, but as Indian Removal continued and the southern slave states colonized more land, a divide would be brought between Black and Native peoples. This divide would ultimately weaken our resistance — forcing the relocation of most Seminole tribes and the fleeing of Black peoples to free states and nations.

But if we want to progress forward today, we must start from a place of shared resistance.

As a black mixed person living in the United States, I have come to understand that my civil rights are linked to the sovereignty and struggles of Native nations.

For many Native peoples, sovereignty is the ability to manage one’s own affairs and determine one’s own destiny; to live unencumbered by the power or influence of another when determining their fate. Yet this has not been the relationship between the United States and Native peoples. The U.S. defines Native sovereignty within the construct of “tribal sovereignty,” labeling Native peoples as “domestic dependent nations” existing within the borders of the U.S. as “wards of the State” — a fundamentally incongruous approach, as one cannot be both “sovereign” and “ward.” Even the word “tribe” is legally contrived and intentionally used by the U.S. as a replacement word for “nation,” though the words do not carry the same weight. This is an age-old form of state-sanctioned violence which aims to dehumanize Native peoples through words and legal constructs.

Black Folks, does this sound familiar? Slavery was a legal construct with dire physical and generational consequences which still persist today. The Emancipation Proclamation is a legal construct which made those who were inherently free legally free in word. U.S. law has repeatedly been used to infringe upon the basic human rights of Native and Black peoples to be free. Even those laws and legal constructs meant to enshrine the rights of Black and Native peoples have failed to acknowledge the inherency of our freedom and therefore fail at their root to protect us.

So, what does this have to do with Black Lives Matter — a movement of Black peoples against police terrorism and state sanctioned violence?

If we want to progress forward today, we must start from a place of shared resistance. Click To TweetIf the United States will not honor the sovereignty of Native nations, then why would the U.S. honor the Civil Rights of Black peoples stolen and brought here as property? Civil Rights are legislated protections to guard the basic civility — which is arguably less than the human rights — of those who have been dehumanized and treated as property for centuries. “Civil Rights” is a legal construct named after the notion of “civility” or “formal politeness and courtesy.” “Sovereignty” is one’s inherent freedom from the control of another, the right to determine one’s future, and one’s supreme power over a body politic.

“Sovereignty” is foundational to our human existence and is not a subjective concept — either you are free or you are not. Native peoples were here first. Their claim to this place is supreme. If the U.S. refuses to honor their sovereignty, the supreme claim of Native nations, the United States will not flinch to revoke the Civil Rights and freedoms of “formerly” enslaved Black peoples and their descendents based on a somewhat subjective notion of “civility.” Therefore, we need each other. We need to stand with each other. We need to learn from our shared history remembering the times when our unity strengthened our capacity to effectively resist our common enemies.

Our movements are not separate. Rather, they are inextricably interconnected. We need each other if we are to free ourselves from the yoke of genocide and enslavement in this place we call the United States. Police terrorism and mass incarceration are really just an extension of this country’s original sins. While young Black people were killed at a sharply higher rate than any other group in 2016 in the United States, the murder of Native people by police also increased. With less than 1% of the United States being Native to Turtle Island, any increase in police murders of Native peoples is deeply painful and a continuation of genocide.

Due to the insidious nature of anti-blackness in nearly every community, including Native communities, it is easy to feel protective of Black movements and our current hypervisibility in our pursuit for justice. That said, Native peoples have always been made hyper-invisible by way of erasure and national amnesia. This is how non-Native settlers make sense of living on stolen land amongst the relatives of genocided peoples. As Black peoples, we must be willing to push back against this erasure, even if it means sharing a hashtag. At the same time, Native peoples must be willing to push back against anti-blackness — a tool used by the white supremacist system to divide and enslave. If we are to share our movements in a meaningful way, we must also take accountability for the ways in which we have internalized white supremacy and colonialism, thereby perpetuating harm against each other.

The organizing efforts of Not This Time, a campaign initiated after the killing of Che Taylor by Seattle Police, is an important example of how Black and Native solidarity strengthens our movements. Not This Time organizers — along with the Puyallup, Muckleshoot, and other Co-Salish tribal nations — have been signature-gathering for I-940, known as “De-Escalate Washington,” a ballot measure which would allow police to be prosecuted for unjustified deadly force. Local tribal nations have donated approximately $285,000 to the campaign and provided hundreds of hours of volunteer time. On December 28, Not This Time delivered 355,000 signatures to the state, qualifying I-940 for consideration. The organizing efforts and success of I-940 thus far illustrates how Black and Native communities can work together to end police terrorism.

In the end, I do not view #NativeLivesMatter as a co-optation of #BlackLivesMatter. It is NOT the same as #BlueLivesMatter, which is a direct affront to our movement to end state-sanctioned violence and police terrorism. It is NOT the same as #AllLivesMatter, which is an attempt to discredit our claim of systemic oppression and targeted state-sanctioned violence — crimes of which both Black and Native peoples are historical and present day victims.

We often say that when Black people get free, we all get free. Likewise, I believe that when the sovereignty of Native nations is recognized, the sovereignty of all beings impacted by U.S. imperialism will be recognized.

Since the inception of this country, the struggle and the enemy of Native and Black peoples has been one in the same. Our survival and thriving depends on our willingness to share our movements and stand up with and for each other.

#BlackLivesMatter #NativeLivesMatter #JusticeForJasonPero #CheTaylor #ReneeDavis #CharleenaLyles