In the current media climate, writers often must rely on government assistance.

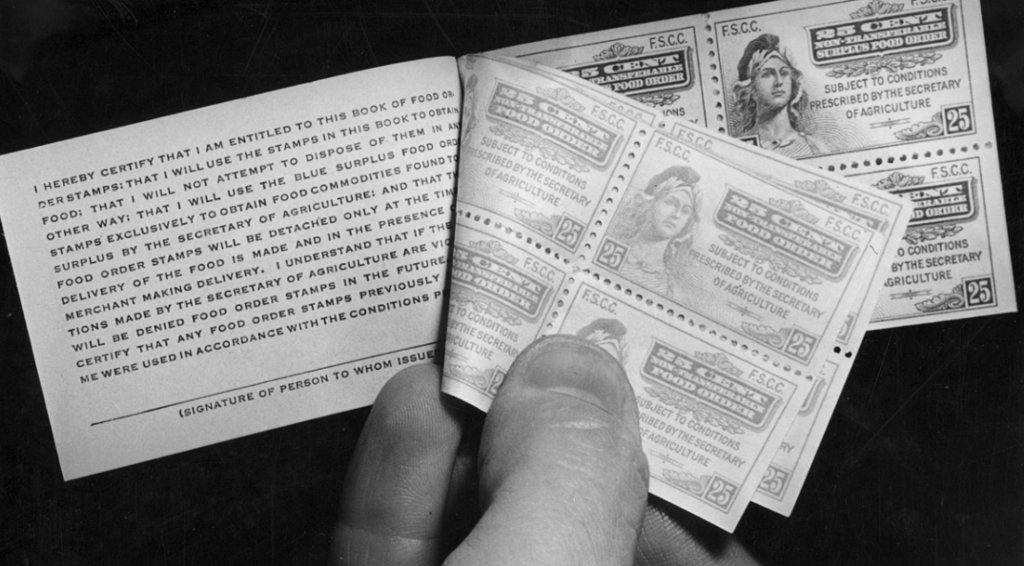

Wikimedia Commons

Erica Langston went on food stamps after finishing a yearlong teaching fellowship in spring 2014. Twenty hours a week working at a ranch — and 15 hours writing — couldn’t pay the bills for the full-time grad student. Langston, a freelance journalist who was previously a fellow at Audubon and Mother Jones, says she couldn’t have focused on writing without government assistance.

“That upsets a lot of people,” she tells me. “The ability for me to step back and say, ‘I’m going to focus on writing. I’m going to continue to pursue writing.’ I don’t know that I would have been able to do that without food stamps.”

Until fall 2015, Langston was among the handful of freelance writers across the country relying on the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP). While statistics on writers specifically are hard to find, an estimated 12% of freelancers in the Freelancers Union, a national labor organization, used public assistance in 2010. Langston, meanwhile, estimates that a quarter of writers in her circle have used or applied for SNAP.

And these numbers don’t even fully reveal the extent of the situation. Some freelancers are eligible for food stamps, but don’t use the benefits. Others are just a few steps away from qualifying.

The need for public assistance reveals how society fails to value professional writers and their economic struggles. As outlets ask freelancers to write for cheap or free and struggle to pay them on time, some are forced to turn to SNAP to get by.

Why Isn’t ‘Ebony’ Paying Its Black Writers?

Many factors fuel freelancers’ financial burden. The internet offers a glut of writing gigs but a dearth of good pay. Reporting on fields like human rights remains underfunded. Income is inconsistent. The “golden age for freelancing” in the 1990s has faded.

Nickel and Dimed author Barbara Ehrenreich saw her rates at one major publication drop by a third between 2004 and 2009. To boot, some outlets spend little on writers relative to their profits. According to Scott Carney, author of the Quick and Dirty Guide to Freelance Writing, the lucrative media conglomerate Condé Nast spends just .6% of its revenue on writers.

The fault lies with readers, too, who have come to expect access to news sites sans paywalls, essentially demanding that writers perform free labor for their enjoyment and edification.

Under such conditions, it’s little wonder that — according to a 2016 Contently survey — 35% of full-time freelancers make less than $20,000 a year.

Why Should You Become An Establishment Member For $5 A Month?

And it’s not just that wages are low; at the same time, living costs are increasing rapidly. According to a recent report, more than 21 million Americans, a record number, spent a staggering third or more of their income on rent in 2014.

To take but one example of how these forces manifest for freelance journalists, Ryan McCready estimated on Venngage that a writer making $0.25 a word would have to write 13,340 words in a month — about the length of Macbeth — to live in Portland.

Troublingly, this paradigm in turn keeps marginalized people from being able to become freelance writers in the first place. Langston sees being able to live paycheck to paycheck and pursue her passion of writing as a privilege; she has a graduate degree and a partner to fall back on during tough months. Not everyone enjoys such luxuries.

As outlets ask freelancers to write for cheap or free and struggle to pay them on time, some are forced to turn to SNAP to get by.

In a cruel bit of irony, even stories about poverty are often written by the financially privileged—it turns out those in poverty are too poor to write about being poor. This not only pushes out perspectives that may have not been considered, it can drive away readers who assume the news is elitist.

In an article for the Guardian, Ehrenrich wrote:

“In the last few years, I’ve gotten to know a number of people who are at least as qualified writers as I am, especially when it comes to the subject of poverty, but who’ve been held back by their own poverty . . .

There are many thousands of . . . gifted journalists who want to address serious social issues but cannot afford to do so in a media environment that thrives by refusing to pay, or anywhere near adequately pay, its ‘content providers.’”

Veteran journalist Darryl Lorenzo Wellington, who worked as a parking lot attendant before reviewing books for the Washington Post for a decade, has seen firsthand how publishing shuts its doors on the under-privileged. He goes to writers’ conferences, he says, where he’s asked where he got his master’s degree; he has just a high school diploma. Magazine editors ask him to put $3,000 or $4,000 in reporting expenses on his credit card, so they can reimburse him — but he doesn’t have a credit card. Recently, a colleague asked him to Skype; he couldn’t drop $200 to fix his broken computer, so he asked her if they could talk on the phone instead. She almost seemed insulted, he notes. “And ironically, that person wanted to do a story about poverty.”

Another downside to low-paid freelance writing is that many are pushed away from crucial reporting because they can’t financially justify the work.

Veteran investigative journalist Christopher D. Cook says he started mixing contract writing with editing and teaching to get by. This diverse income keeps him off the food stamps he once relied upon — but it also means he’s unable to do as much investigative work as he once did.

“That’s a terrible position for society to be in, where it’s not economically feasible to have investigative reporting,” says Cook. “It’s central to our society and our democracy to have people be able to survive as journalists.”

When Predators Exploit Freelance Writers

It looks like this issue will only become more dire in the coming years; as experts expect half of the U.S. workforce to freelance in some capacity by 2020, the Trump budget plans to cut SNAP by $190 billion over the next decade.

So what can be done to support writers and their work?

Carney thinks that freelancers could do more to advocate for themselves, to negotiate a fair, well-paying contract once their story’s accepted. After going without health insurance for a decade, and at times having $12 in his bank account, he says valuing his own work helped him reach middle class.

“The world isn’t essentially fair. You get more if you fight for more,” he says. “If freelancers are willing to sell themselves for pennies on the dollar, then magazines are happy to take advantage of that.”

I’m Too Busy Being Poor To Be Creative

But of course, real progress can’t happen without changes to the system itself. Some suggest safety nets like guaranteed health-care coverage, a universal pension, and more grants for struggling freelancers. Currently, PEN America is among the few groups that offer emergency funding to writers.

Others say freelancers should unionize, or online outlets should experiment more with new revenue streams to have money to pay their writers more.

Workers’ rights attorney Paula Brantner adds that freelancers should be able to file wage claims, like employees. They should have a remedy beyond suing in small claims court if they aren’t paid for the work they do.

And Wellington thinks the government should offer everyone who makes, say, $25,000 or less annually a food allowance.

At the same time, we need to talk more candidly about the financial realities of freelance writing, and work toward the crucial de-stigmatization of poverty.

We need to talk more candidly about the financial realities of freelance writing.

For freelancers like Erica Langston, food stamps aren’t part of a lifetime of poverty, and due to lingering societal stigmas, it can be tempting to try to create distance from the chronically impoverished. This reveals a deep-seated classism that holds both the publishing industry and society back.

In 2015, Langston tried to use her electronic benefit transfer card at the grocery store, but the company had just changed the system, and the clerk had to put it in manually.

“I felt so uncomfortable in that moment. I was holding up the line. I handed over my food stamp card. I don’t know if anyone noticed. I don’t know if anyone gave a shit. But I had this internalized feeling that I was being judged because of that. And I even felt guilty because I wanted to explain in that moment, ‘No, no, you don’t understand. This is just temporary . . . ’

The fact that I would feel the need to explain that says a lot about the system in general. I mean, it’s temporary for me, but it’s not temporary for some people, right?”

Langston is one of many freelance writers who remain a step away from struggling to put dinner on the table. Others already can’t feed themselves. As the gig economy rises and government assistance wanes, will companies find a way to meet independent contractors’ basic needs?

And more importantly, what will happen to media if they don’t?

Looking For A Comments Section? We Don’t Have One.