To read this content in Comic Sans, thanks to one of our awesome readers (That means you, Abby!!), click here.

It’s cool to hate comic sans. But it’s also problematic.

The day my sister, Jessica, discovered Comic Sans, her entire world changed. She’s dyslexic and struggled through school until she was finally diagnosed in her early twenties, enabling her to build up a personal set of tools for navigating the written world.

“For me, being able to use Comic Sans is similar to a mobility aid, or a visual aid, or a hearing aid,” she tells me while we’re both visiting our family in Maryland. “I have other ways of writing and reading, but they’re not like they are for someone who’s not dyslexic.”

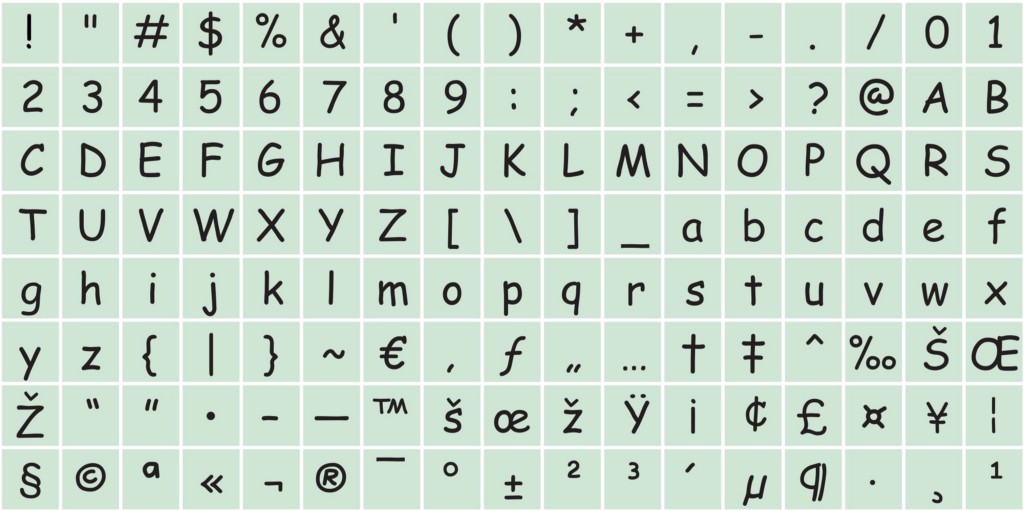

The irregular shapes of the letters in Comic Sans allow her to focus on the individual parts of words. While many fonts use repeated shapes to create different letters, such as a “p” rotated to made a “q,” Comic Sans uses few repeated shapes, creating distinct letters (although it does have a mirrored “b” and “d”). Comic Sans is one of a few typefaces recommended by influential organizations like the British Dyslexia Association and the Dyslexia Association of Ireland. Using Comic Sans has made it possible for Jessica to complete a rigorous program in marine zoology at Bangor University in Wales.

The day my sister discovered Comic Sans, her entire world changed. Click To TweetYet despite the fact that Comic Sans is recommended for those with dyslexia, the gatekeepers of graphic-design decency routinely mock those who use it as artistically stunted and uneducated.

It turns out the ongoing joke about the idiocy of Comic Sans is ableist.

Microsoft font designer Vincent Connare created Comic Sans — based on the lettering by John Costanza in the comic book The Dark Knight Returns — to be used for speech bubbles in place of the unacceptably formal Times New Roman. The font was released in 1994.

“Comic Sans was NOT designed as a typeface but as a solution to a problem with the often overlooked part of a computer program’s interface, the typeface used to communicate the message,” Connare says on his website. “The inspiration came at the shock of seeing Times New Roman used in an inappropriate way.”

Today, Comic Sans is the font everyone loves to hate. There’s a petition to ban it from Gmail and myriad stories about how terrible it is. Even Weird Al chastises people who use Comic Sans in his music video for “Tacky.” (“Got my new résumé/it’s printed in Comic Sans.”)

A Ban Comics Sans movement began in 1999 with graphic designers Holly and David Combs. In a 2010 interview with The Guardian, Holly said, “Using Comic Sans is like turning up to a black-tie event in a clown costume.” Their manifesto states, “By banding together to eradicate this font from the face of the earth we strive to ensure that future generations will be liberated from this epidemic and never suffer this scourge that is the plague of our time.” Their website sells t-shirts for anyone who wants to drop $26 to make sure their stance on this font plague is clear.

There are other websites dedicated to ridding the world of Comic Sans as well, including a Ban Comic Sans Tumblr page and ComicSansCriminal.com. The latter frustratingly has “Alternative Dyslexia Fonts” on its nav bar, as if acknowledging that attacking Comic Sans disadvantages those who are dyslexic is enough to absolve the site of its ableism. (It is not.)

The line of thinking behind these movements is “quite elitist,” Jessica says. “It’s belittling and condescending.”

The line of thinking behind anti-Comic Sans movements is elitist, belittling, and condescending. Click To TweetI asked Jessica to tell me what she’s up against. She’s been told that Comic Sans is “unprofessional. That it’s juvenile. That it’s stupid. That it basically shouldn’t be used for anything at all, unless it is a comic.”

There are fonts that have been specifically created for people with dyslexia, all of which lack the clean minimalism or elegant balance and perfect kerning favored by typography snobs. But they are crucial disability aids. Some are free, such as Lexie Readable (which calls itself “Comic Sans for grown-ups”), Open-Dyslexic, and Dyslexie. Others are for purchase or are publisher-owned and unavailable to the general public.

But for Jessica, Comic Sans is still the best. “I don’t use Open Dyslexic because it’s not as easy for me to read,” Jessica says. “It’s not my font. I was dyslexic before Open Dyslexic happened. My mind has been getting used to Comic Sans.”

Not everyone with dyslexia uses Comic Sans to help them read and write. “Other people with dyslexia find that having colored paper makes it easier,” Jessica says. “Or some people find Arial easier.”

Comic Sans and Arial are readily available because they are included by default in many operating systems and word-processing programs, and they are web-safe fonts. A pamphlet from the office of student services at my sister’s school on accommodations for dyslexic students is printed in Comic Sans on blue paper in both English and Welsh. Other common fonts suggested by the British Dyslexia Association include Century Gothic, Verdana, Calibri, and Trebuchet. (Trebuchet was also designed by Connare.)

According to my sister, the truly villainous font is the ubiquitous Times New Roman. “I don’t know anyone [dyslexic or not] who reads Times New Roman well. It’s definitely my least favorite font.” To her, the serifs turn the text into a dense blur at small sizes. My sister tells me of a particular time Times New Roman made school unnecessarily difficult for her during a tutorial on scientific data analysis and graphing software.

The truly villainous font is the ubiquitous Times New Roman. Click To Tweet“The lecturer printed out these handouts in Times New Roman. Everyone’s like, ‘Oh my god. This is so easy!’ I handed him the thing back and I was like, ‘It’s not that your instructions are difficult, I cannot read them. I’ve nearly cried three times during this.’”

Since the handout was available online, she was able to modify it into a readable format.

“What I did is I eventually downloaded the handout, blew it up to 16 point font, turned the paper green, and turned it into Comic Sans.” Then the assignment became just as easy as it was for her classmates.

Sometimes people ask Jessica why she doesn’t begin in Comic Sans and then hand in her papers in Arial or Times New Roman.

“Have you ever tried to format a scientific paper when you have to get everything lined up so specifically? You’ve got all of your legends that have to go underneath your figures. 12 points in Comic Sans is not 12 points in Arial is not 12 points in Times New Roman. You can spend hours formatting your paper in Comic Sans and then turn it into 12 point Arial and it will mess up everything.”

In addition, she cannot proofread in a font that’s difficult for her to read. “You cannot fix formatting errors you cannot see!” To her, asking her to change to a font she cannot adequately use “is the epitome of ableism.” Sometimes she can ask someone in her cohort to help her spot errors, but it’s a lot to ask. “I can and have had people in my class look over my work, but you need to understand that we’re not collaborators, they’re my peers. This is an encroachment on their time.”

Asking her to change her font is asking her to take a task that is already very difficult for someone with dyslexia and demanding that she take extra steps to please the aesthetic preferences of someone for whom reading is easy.

“If you work with someone with dyslexia, maybe even if you don’t know if they’re dyslexic, if something is laid out well, if someone has gone through the time to carefully format something, please accept it in whatever color, whatever font people want to use. You never really know what is helping someone. If it’s not hurting you, then just leave it alone.”

People without dyslexia need empathy for those who need concessions to manage the disability. “You have to think about how massive this issue is for me, and you have to think about how tiny the issue is for you.”

In summary, she says:

“Get the fuck over yourself.”