The gender segregation of the H2-A and H2-B visas, along with a lack of equal protections, leave temporary migrant women to suffer.

Carolina Algara* wanted to work almost anywhere but the chocolate factory in Louisiana, but that’s what she did, for four years in a row.

Each year, recruiters for the United States’ temporary work visa programs would arrive in her rural town in central Mexico and offer the men options for jobs north of the border: in farming, forestry, landscaping, carnivals, hotels. And each year, the women (with their “nimble fingers perfect for delicately sorting chocolates”) were offered only the factory.

“It was my only option—I didn’t know what else to do,” Algara said. “Recruiters would say outright, ‘No, I don’t have opportunities for women—these positions are only for men.’”

The chocolate factory—like many companies willing to hire migrant women under the H2 visa programs—paid badly, offered no overtime, and had no tolerance for complaints or illness. After speaking out about the conditions in the chocolate factory, Algara was not hired to return for a fifth year.

For Algara, and for countless migrant women like her, the initial discrimination during recruitment served as an introduction to a part of the U.S. immigration system where equal protection under the law is nothing more than a catch-phrase. When it comes to the H2 programs (H2-A and H2-B for agricultural and non-agricultural work, respectively), women consistently get the short end of the stick: in everything from job placement to task assignments, and from sexual harassment to wage allotment. And yet, they continue to return, filling the perennial labor needs of a system that disincentivizes their participation.

“In Mexico in particular, discrimination across the board is very commonplace,” said Julia Coburn, director of operations for worker advocacy organization, Centro de los Derechos del Migrante (CDM), and coordinator of CDM’s Migrant Women’s Project. “But I think in the United States, discrimination across the board is very commonplace as well. It’s something that we see in jobs of all types, all around the country, but it is especially pronounced in the H2 visa programs.”

When it comes to the H2 programs, women consistently get the short end of the stick: in everything from job placement to task assignments, and from sexual harassment to wage allotment. Click To TweetThere are three main steps (and three main bureaucratic actors) in the H2 visa approval process. First, an employer hoping to utilize temporary labor petitions the Department of Labor (DOL) for foreign labor certification. During this process, the employer is required to show that their need is temporary, and that they have already tried (and failed) to recruit U.S. workers. Second, the employer submits a petition to the U.S. Department of Homeland Security (DHS) to finalize approval. Finally, prospective workers apply for visas through the Department of State, via the government of their home country. As of January 2018, there are 83 countries eligible for H2 visas.

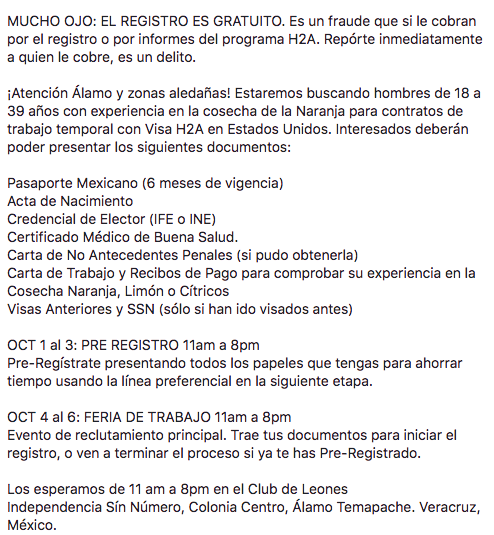

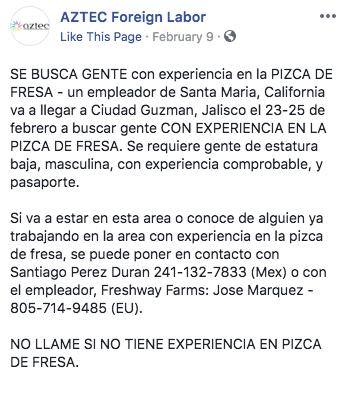

In Mexico, one of the biggest markets for temporary labor, it is common for a recruiter to serve as the middle-man between labor and bureaucracy. Companies who have been allotted a certain number of visa slots hire recruiters, who tend to have a license to recruit in a town or region in Mexico. The process is chaotic; migrants talk of announcements on village loudspeakers, hours in line under the hot sun, over 200 dollars (4000 pesos) pressed into recruiters’ hands to save a spot in the visa application process. Even those who return to the U.S. year after year are subject to this dysfunction.

When workers arrive, their legal status is entirely tied to their employer; they cannot change positions or companies. Workers typically reside in the U.S. for just a season, and many have families that they support during the off-season with their wages from their work north of the border. A September 2017 report by CDM and the University of Pennsylvania’s Transnational Legal Clinic showed that women were particularly likely to be supporting families—94 percent of those surveyed (which included all visa categories aside from the J1 ‘au pair’ program) spent an average of 70 percent of their earnings on “childcare and other family support.”

While H2-A and H2-B visas are both temporary worker programs, the H2-A program is considerably larger. Consequently, H2-A workers have more resources at their disposal: more specialized legal assistance programs, higher wages, and simply better strength-in-numbers. It is widely considered the better visa.

“They have an opportunity to earn more,” explains Coburn. “Often H2-A workers in communities in Mexico are considered privileged; they come back with more money over the average season.”

According to Coburn, in practice the distinction between the two categories translates to significant disadvantages for women, because H2-A visas rarely go to women (only about three to seven percent). Instead women are slated into non-agricultural H2-B jobs, which typically amount to stereotypical “women’s work,” like Algara’s work in the chocolate factory.

Even when men and women work in the same workplace—as is the case in the crab industry—men are given the chance to earn overtime pay for their roles lifting and cooking crab. Silvia, an H2-B worker who did not give her last name, told CDM that men frequently were given more hours of work that the women who worked on the Eastern Shore of Maryland. Men are also more often paid by the hour. Women, in contrast, are typically paid a piece rate: usually by the pound of crabmeat picked.

Even when men and women work in the same workplace—as is the case in the crab industry—men are given the chance to earn overtime pay for their roles lifting and cooking crab. Click To Tweet“We’ve even been told that while these men are working longer hours, women are expected to spend their off-time cleaning the men’s housing, or do other unpaid domestic work that’s considered women’s work,” says Coburn.

Algara started working at the Louisiana chocolate factory in 2003, when a recruiter came to her town. A young mother at the time, she hoped to spend a few months each year working hard in the U.S. for an hourly wage far higher than what she could make in Mexico. That seasonal income would help sustain her throughout the rest of the year.

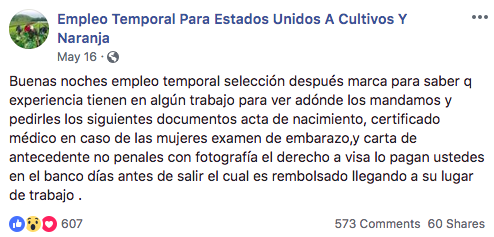

However, recruiters made it abundantly clear that she would only be considered for certain jobs. Recruitment ads on Facebook and similar networks specify that they are looking for “men ages 18 to 39”. One goes so far as to specify that women applicants must include a (presumably negative) pregnancy test with their visa application materials (also pictured).

In Algara’s case, the lack of options led to a loss of economic opportunity. “The truth is that I wanted to do something else,” she says. “In the factory we couldn’t work more than 40 hours per week, so we had practically three days of doing absolutely nothing.” And while the 40-hour workweek is something American unions fought hard for precisely in order to protect workers from exploitation, it limits migrant workers, who cannot pick up a second job if they want to earn more. Daria, who worked packing vegetables on an H2-B visa and also preferred not to use her last name, explained to CDM that she and her female colleagues only worked three to five hours per week, and earned 10 percent less per hour than she had been promised during recruitment.

Algara also felt that her company took advantage of its monopoly power over her cohort of women workers, barely giving the migrants enough work for the whole process to be worth it. However, with few other options, she returned to the U.S. yearly until she was blacklisted by the factory.

Algara rallied 70 of her colleagues to stop work and demand fair labor standards for reasons of gender discrimination (the men earned more for their roles carrying and stacking boxes than the women did packing chocolates on assembly lines), and lack of respect toward workers. These concerns represent just a few of the buffet of problems workers have voiced, which include visa fraud, misrepresentation of contract, failure to provide workers with copies of their contract, and charging workers fees for recruitment.

While these practices are prohibited under U.S. labor law and the North American Agreement on Labor Cooperation (NAALC), the Department of Labor and other relevant bodies simply do not have the resources to investigate all the claims that are made about the H2 program. Several workers, with help from CDM, filed a petition on gender-based discrimination with the NAALC in 2016. They have yet to receive an official response from the U.S. government about that petition (MEX 2016-1) or its supplement under the NAALC. have yet to hear back about its consequences.

(Shortly after filing said petition, CDM got a call from the U.S. government—who ostensibly did not know CDM had helped the petitioners—requesting information on the subject: “we need to reply to this petition, and you’re some of the only people we know working on this stuff.”)

Several workers, with help from CDM, filed a petition on gender-based discrimination with the NAALC in 2016. They have yet to receive an official response from the U.S. government. Click To TweetMigrants like Algara are lobbying to get more explicit protections included in the new USMCA agreement. They celebrated a minor victory this August when the U.S. Trade Representative announced that migrant workers would “ensure that migrant workers are protected under labor laws” in the NAFTA renegotiation, though it is unclear what form that protection will take now that USMCA has been announced.

For now, though, women continue to see the worst of a system that allows for rampant abuse of workers of any gender. They frequently describe their fear of retaliation for speaking out (and with good reason, considering Algara’s experience). And for many, the personal and economic stakes are simply too high to do so, even in the face of wage and hour violations, health and safety problems, discrimination, and even gender-based violence.

So, many women simply grin and bear it—the stakes of losing an opportunity like an H2 visa reach beyond themselves to their families and entire communities. And as for why the companies hosting them get away with the practices that would push workers with more options away? It all comes back to the law of supply and demand, says Coburn.

“If you come with a visa, you have different rights that other people,” she says. “You are constantly reminded that there are thousands of other workers behind you, waiting for your place, just in case you lose or leave your job.”

*Source’s name has been changed to accommodate her fear of further retaliation, should she decide to apply for an H2-B visa again.