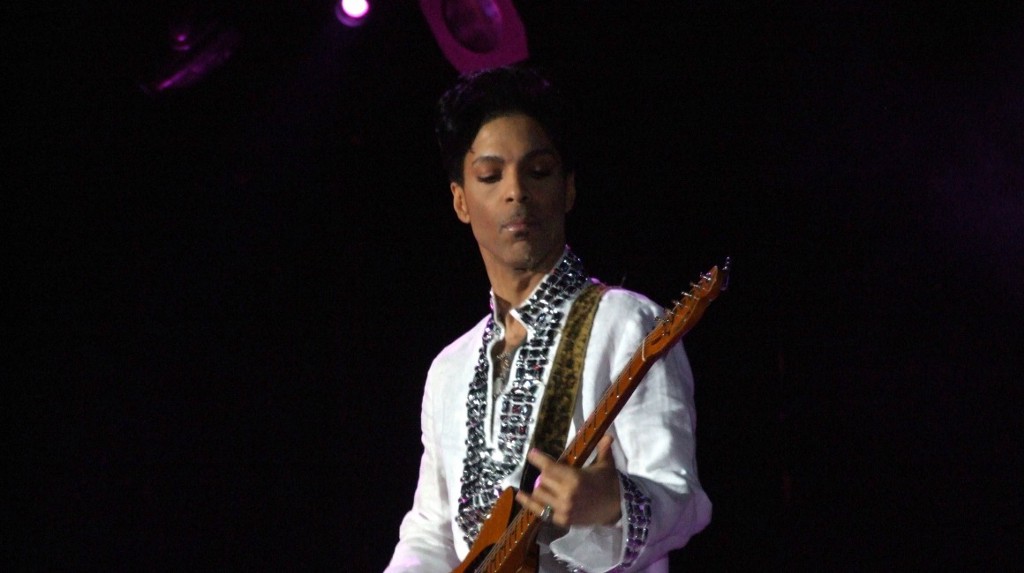

flickr/Scott Penner

By Ijeoma Oluo

I remember it clearly, my white mother talking to her black friends as my brother and I, six and four, played underfoot.

“These kids need to be around you, I’m afraid they won’t learn how to be black.”

I understand now, as an adult, what my mom was saying. My white mother was concerned that she would not be able to raise two black kids fully in their blackness, on her own. Many black children raised by white parents do indeed suffer from being cut off from their heritage, from feeling different and erased.

But hearing those words, at six, I felt adrift. I walked over to the always-on television, and turned it to MTV where Prince was guaranteed to be on within minutes.

By six, I was already an awkward, bookish kid and by four, my brother was already a highly sensitive, creative weirdo. These were our personalities then, and they are our personalities today. But for many people we encountered, our very personalities were a sign that our “blackness” had never fully developed.

To kids at school we weren’t “really black.” Older black folk shook their head at our weirdness, “This is what happens,” they would say, “when black kids aren’t raised right.” White people saw us as black, but as the stereotypical idea of black that they were comfortable with — so they didn’t see us at all.

And at an early age, my brother and I both desperately wanted to prove ourselves to our community, but we didn’t know how. We were who we were, and we were made to feel like we were broken.

But even at six, I had an idea that there might be a place for us. I didn’t know where Lake Minnetonka was but I knew it was home. Watching a black man in lace and ruffles and leather slide across the screen in complete confidence was a revelation to me. He owned the screen and the stage, and he was so damn weird. Everything that my brother and I were told not to be as black kids, he was. He was sensitive, he was flamboyant, he was sexy, he was bold, he was as feminine as he was masculine. He lived in a place where nobody questioned why his voice didn’t sound “black enough,” he lived in a place where nobody asked why a black dude would love rock n’ roll, he lived in a place where nobody told him to “toughen up” the way they were always telling my brother, he lived in a place where he could wear heels and lace and eyeliner and nobody told him to “be a man.”

And nobody questioned Prince’s blackness. Not a single person.

The same people who bullied my brother and me for not being “black enough” sat next to us to watch “Purple Rain” time and time again. The same people who just this week were pulling up pictures of my once blue hair and lighter skin in order to revoke my “black card” are likely listening to “Let’s Go Crazy” today and mourning the loss of an undisputedly black man who defied all their norms. Prince was my safe haven at six; he helped give me the confidence to be who I am today.

Prince was, and is, magic. He got the entire world dancing and singing along to a music that defied genre, played by a man who defied every constraint placed on black and male identity. He was a beacon for all of us who were told that we must cut out a part of ourselves in order to fit. I never considered a world without Prince, it did not seem possible that a man made of art and beauty and sex and the boldest chords and the brightest colors could ever die.

Prince will live on, in the hearts of every music lover in the world, and in the defiant existence of black weirdos everywhere.

So many of us exist, as we are, because of him.