Whitman was haunted by the prospect that we would lack a ‘common skeleton.’

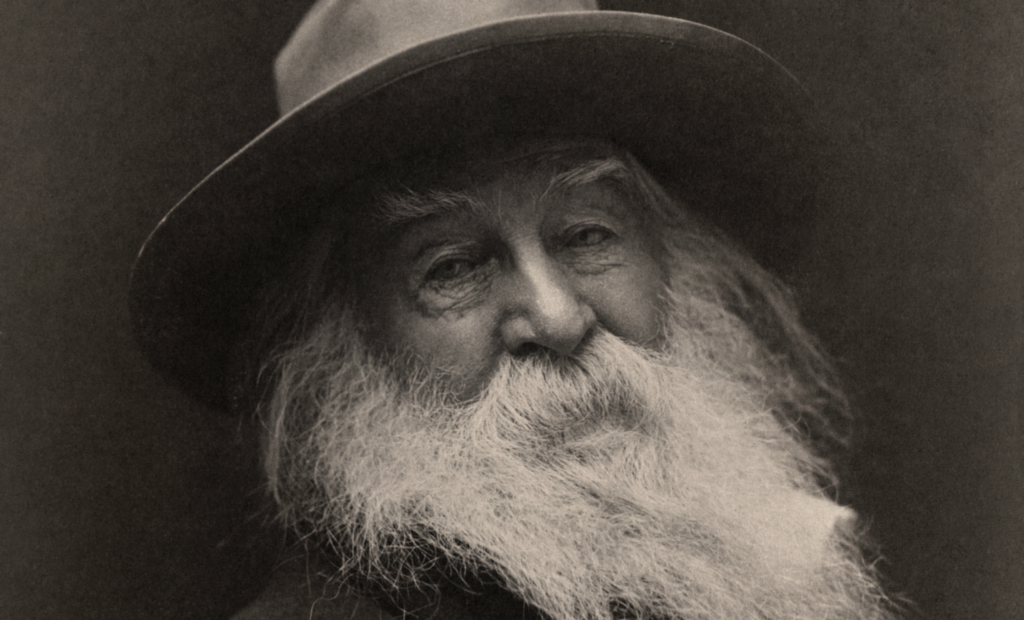

I often imagine myself in the company of the poet Walt Whitman. Sometimes I’m seated beside him on one of those New York City tour buses he was so fond of riding; sometimes we’re standing at the rail on the Brooklyn Ferry looking back at our wake; sometimes we’re on the Montauk shore, our legs stretched out toward the horizon, the waves leaving shards of shell and bone at our feet.

I ask him, “So, how’s America doing?” And I imagine his long sigh.

In 1871, Whitman wrote his essay “Democratic Vistas,” which articulated his hope for his fledgling nation and expressed his fears and concerns in regard to its post-war, materialistic present — and its future.

Best known for his sweeping democratic poem “Song of Myself” and now known as the “father of American poetry,” in his youth Whitman was enraptured by the physical realities of America — its diverse human bodies and backgrounds, its prairies, its seas, its chaotic urban centers and the frenzy of individuals who populated it.

Whitman was enraptured by America — its diverse human bodies and backgrounds, its prairies, its seas, its chaotic urban centers and the frenzy of individuals who populated it. Click To TweetLike other abolitionists at the time — such as Abraham Lincoln and John Brown — Walt Whitman’s words sometimes reflected the “science” and dominant worldview among the white population of his day, which assessed Black people to be inferior to whites. While Whitman also openly questioned these commonly held beliefs and advocated for slaves’ freedom, there is a strain of thinking in some circles of academia and popular culture that perceives Whitman to be a controversial figure in terms of racism.

While acknowledging the abhorrence of such racist views, I also believe that dismissing the entirety of Whitman’s work on these reductive attitudes would be a waste—and reading his work immediately reveals why. In fact, during his lifetime Whitman avoided publishing work that addressed race because, according to George Hutchinson and David Drews, it was “as if Whitman did not trust himself on racial issues and therefore largely avoided them […] he wanted to revitalize American culture and finally to be remembered as democracy’s bard.”

In America’s stunning diversity, Whitman saw an intricately beautiful mirror of the universe’s complicated grandeur. Yet, in this variety he also feared an insurmountable division. Whitman looked at the expanse of the country — its wide-ranging regions, economies, subcultures, and individuals — and foresaw the challenges we would face in becoming truly united. He worried that we would fail to join under a common “idea” of who we are, and he was haunted by the prospect that we would lack a “common skeleton.”

Emily Dickinson’s Legacy Is Incomplete Without Discussing Trauma

It is quite obvious given our last, intensely divisive and vitriolic election — and its continuing crushing fallout — that we as a people are not united by one Idea of what America is or should be. And at this point, we might be wondering how fusing 330 million polarized people could ever be possible. But in addition to expressing his concerns for our unity, Whitman also proposed a solution.

In his essay, Whitman argued that what would unite the diverse people of the United States would not be “Constitutions, legislative and judicial ties, and all its hitherto political, warlike, or materialistic experiences,” but a greater “moral identity.” And he theorized that this would be possible only through what he called our “national expressers”: “a cluster of mighty poets, artists, teachers, fit for us.”

People capable, as Transcendentalist philosopher and essayist Ralph Waldo Emerson explained, of seeing a whole from all of the parts. Visionaries. Those who British poet Percy Bysshe Shelley called “the great legislators of the world.” These people, Whitman believed, would understand and effuse “for the men and women of the United States, what is universal, native, common to all.” At a time when there seems to be the perception that everyone is pushing their own agendas and needs or wants wildly divergent things, how can we know what’s common to us all?

If we take Whitman’s cue, we might consider reading and listening to the voices of our great expressers. Voices like Walt Whitman himself and Martin Luther King Jr. Voices like Adrienne Rich, Muriel Rukeyser, and Emily Dickinson. Voices like John Steinbeck, Nathaniel Hawthorne, and Audre Lorde.

Whitman was haunted by the prospect that we would lack a ‘common skeleton.’ Click To TweetBut I can tell you that from my experiences as a writer and teacher of literature and the humanities, fewer and fewer of us have any experience with America’s “national expressers.” Perhaps the resistance and suspicion we feel toward each other, toward journalists, artists, teachers — toward very truth in general — perhaps the doubts we express in each other’s intentions is a result of us not communally sharing in the celebration of our humanities, our poetry and art, in the first place.

There is a growing trend in this country, a resistance and even hostility, toward intellectualism, reason, and the very same people who would be our national expressers — teachers, poets, writers, artists, even lecturers — as less and less of the population reads these expressers’ expressions, the words of our great teachers.

This is in part due to massive funding cuts to our humanities departments and courses. On top of that, it’s not uncommon for college students’ parents today to demand that their children not “waste their time” (and money) in such classes. And more people who actually do attend college focus solely on an area that will increase their chances of attaining a job that will pay higher wages.

If we suppose Whitman is right — if the common appreciation and understanding of our humanities is necessary for a unified country — then the less familiar people are with these voices, the more divisiveness ensues. In short, we’re experiencing exactly what Whitman feared.

Today, as I continue to process what the election of Donald Trump by one quarter of eligible American voters means for our future, as I reflect on my years of teaching college at state universities, private colleges, and community colleges, I think about my students — fresh out of high school, still in high school, retired, midlife, black, white, Muslim, statist, trans, autistic, rich, poor, formerly incarcerated, recovering alcoholics, Spanish-speaking, Portuguese-speaking, a new mother.

I think about the diversity of people I’ve had the pleasure of introducing to literature and poetry — to Whitman — and in turn, when they compose their own poems and essays, introducing them to their own voices, and when they peer review and give presentations, to each other’s.

In these classroom communities, all of us work together despite our differences. We learn from each other, laugh together, and better ourselves through each other and the voices we read. We discover new worlds that comprise our one world. It’s not that we have to agree with everything we read or hear; it’s simply that we acknowledge that such exchanges and bodies of work exist—and respect that. That we become aware of parts different from us that make up our whole. The college classroom — and especially one studying the humanities — is a place where differences become our wealth, and potentially, ideally, strengthen our moral compasses.

The Artist Behind The Establishment’s Official Love T-Shirt Believes In The Power Of Every Body

College, of course, is not the only way to read America’s great voices. But in an age of decreased interest in reading and mental solitude, increased time on social media, and fewer opportunities to participate in discussions with diverse individuals, it remains one of the surest bets—not to mention its material rewards. A college education translates not just to more money (on average $32,000 more per year), but the probability of being employed is 24% higher; those with a college education are also twice as likely to volunteer their time or work for a non-profit.

And in our ever-diversifying world, a college education also permits opportunities to commune with people unlike oneself that otherwise might not present themselves on a daily basis.

Yet, in America today college enrollment is decreasing. According to CNN, there are over 800,000 fewer college students in 2016 than there were in 2010. And as of 2014, just under 42% of American citizens held a college degree. As the system continues to fail millions of American citizens, we highlight the systematic devaluation of education, which threatens our collective morality.

This is largely, of course, due to the alarming spike in tuition rates. But it’s also rooted in a lack of fair compensation for teachers. We may be used to hearing the lament about salaries in regards to high school teachers being underpaid, but it is also true of college instructors. According to the AAUP, 70% of college professors are adjuncts, part-time, or temporary. These teachers are almost always underpaid, under or totally uninsured, and overworked as they cobble together low-paying classes from various colleges to survive financially.

Whereas the norm used to be to teach two or three classes per semester, it is becoming more common for professors to teach six or seven. There is also a growing perception in America today that college — viewed as an investment with the expected return of a high-paying job — is a waste of time and money. Not unlike Whitman’s time, there is a preference for money and material wealth over empathy and learning for learning’s sake. In turn, we are separating ourselves and our children from the voices of our shared human past that actually unite us. We are silencing our own voices.

We are separating ourselves and our children from the voices of our shared human past that actually unite us. Click To TweetA voice inside asks me how it’s possible that Mr. Trump — a sexist, racist, xenophobic, authoritarian, woefully inexperienced public leader — was chosen to represent all of us. But that voice is quickly answered: Trump doesn’t. Hillary doesn’t. These are not our national expressers — people want actual, real change. I live in Michigan, where Bernie Sanders won the Democratic primary and where 48% of voters filled in a circle next to Trump/Pence, enough to for the state’s electoral votes to go Republican.

The majority of us — blue and red — are unhappy. But why is the change we hope for so disparate when we live in the same country? How could the least moral candidate on the ballot be chosen to represent us morally?

Today, in an America more diverse than ever, whether you live in De Moines or Los Angeles, never hearing the work of our “great expressers” not only depletes the richness of your life, but cuts you off from the American story — the stories of all of us; it depletes our nation’s integrity as a whole.

If Whitman were here (and he is — check your boot soles), I imagine he wouldn’t lose faith in the great American experiment. He’d certainly tell us to read his book Leaves of Grass, which in my courses next term we shall.

And I imagine he would also advise us to turn to our great expressers whether in a classroom or on our own; we must invest time and energy to ensure that we all have the opportunity for these pursuits. A college education is currently prohibitively expensive — it’s been said that a mere 17% of Americans believe they can cover the expense of college for themselves or a family member — but it doesn’t have to this way. Making college education more accessible must remain at the top of our collective societal list moving forward.

Making college education more accessible must remain at the top of our collective societal list moving forward. Click To TweetAn American education wasn’t explicitly designed — by Thomas Jefferson or anyone else — to prepare us for the workforce. It was intended to prepare us to act as a responsible U.S. citizen, capable of voting in the best interest of our country and its people. Last election, millions of American people did not do this.

If Whitman were here, he might propose that it isn’t democracy that’s failed, and perhaps not even our educational institutions; one doesn’t need, of course, to be in school to read books. But we have to find a way to unify us in a deeper more fundamental way, through a shared learning of the important works of our past—and our present.

For it is only in unity that Americans can come to understand what Whitman called our common skeleton, and take instruction from our great expressers on how to build it—justly and with equality for all. Because until that happens, we’ll continue to exist as a nation of broken bones.