Sensitivity to language is responsibility to language, and respect for its power to call forth whatever is summoned by its use.

My name is difficult. All my life, it’s been mispronounced, misheard, misspelled. It’s such a common experience that I’m surprised and impressed when it’s represented correctly. When my name is used incorrectly, there’s a way in which I feel incorrect, like my presence is not fully accounted for.

We all have stories about our names and, whether they are difficult or common, our experiences with them help cultivate our identities. For people with names that do not subscribe to English language convention, like writer Durga Chew-Bose, the experience of feeling like an outsider due to the treatment of a name represents a belittling of an “essential sense of self.”

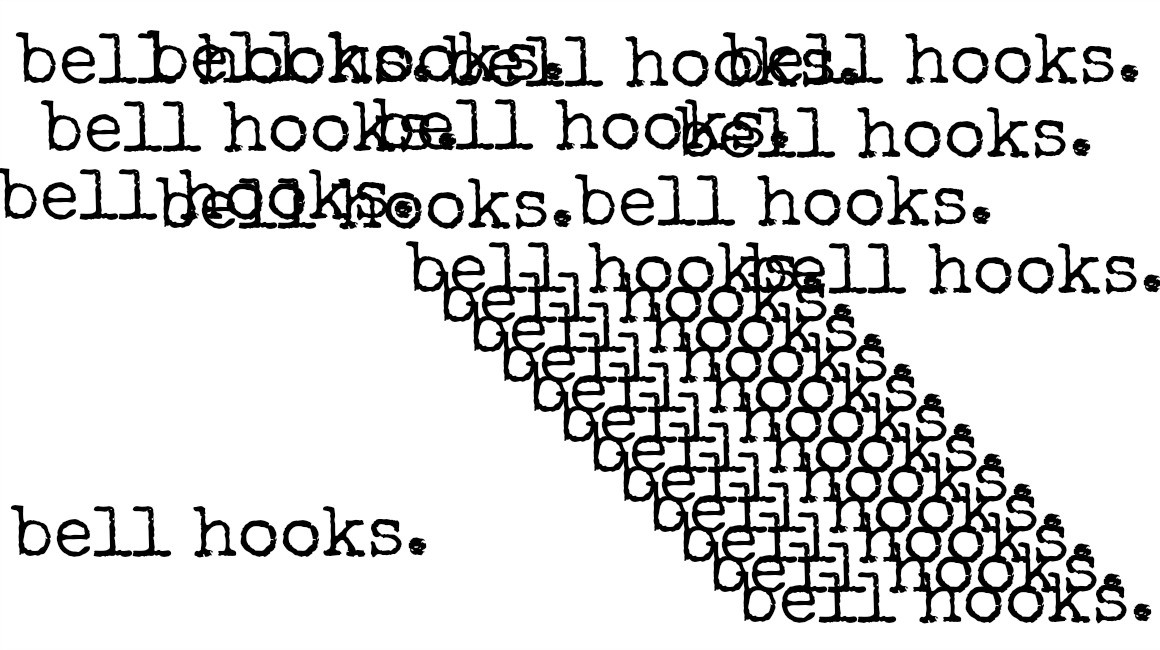

It was perhaps with this acknowledgment of the effect of a name that I found myself defending the correct spelling of bell hooks’ name, which I recently included in a profile I wrote about a comedian. The experience was strange — though I argued with editors about the basic fact of respect and the troubling imposition of capitalization and even sent them links to style guides and other publications that have all honored the correct spelling, they stubbornly believed that their conception of “reader clarity” and “stylistic consistency” superseded the proper presentation of a prominent philosopher’s name.

Eventually, dissent culminated to a point it should have never reached and the editors made the right decision to present hooks’ name accurately — but not without reprimanding and patronizing me for posting publicly about the plain fact of the error and the clear embarrassment I felt as the named author of a piece that meant a lot to me and included this egregious oversight.

We all have stories about our names. Click To TweetThe misrepresentation of hooks’ name amounts to a misrepresentation of, and disrespect for, the educator as a person. That the decision to respect a person by invoking the correct spelling of their name turned into a heated debate perplexed me, though it really shouldn’t have, given that language has always been a site of domination. The experience was a clear embodiment of the exercise of white privilege at a basic systemic level, and it revolved around a writer and thinker whose work seeks to dismantle that very thing. The irony was transparent. (Not to mention the additional irony that lies in the fact that my profile was about the importance of language.)

No matter the reason for hooks’ decision to lowercase her name (according to her Berea College biography, she claims this spelling is meant to draw more attention to her work than who she is), featuring her name incorrectly amounts to a distortion of her identity.

And to distort an identity in the name of grammar is to distort an identity in the name of an imposed convention that has silenced cultures and communities for centuries.

Fundamentally, the power of names is intricately woven into the fabric of our individual and social identities. In many cultures, including the West, the act of naming exhibits dominion or power over something or someone. Examples abound in stories found in mythology, religion, folklore, film, and fiction.

In Greek mythology, invoking the name of the god of the underworld, Hades,summons the god. In the Bible’s Book of Genesis, God names light into being and Adam is tasked with naming the animals of the world in order to exercise man’s dominion. In the Gospel of John, we find the introductory verse naming the Word as God. In fact, A Russian dogmatic sect called the Name Worshippers (heresy according to the Russian Orthodox Church) claim to know that God exists because God can be named. And according to the Kabbalah, the name of every creation is its life-source.

Many stories in popular culture are also rife with powerful name themes. For example, in the Germanic fairy tale Rumpelstiltskin and the 1988 film Beetlejuice, plot is bound up in the way names break a spell or summon a presence. In the novel The Handmaid’s Tale and film Spirited Away, young women are enslaved, the domination inscribed in the act of naming.

One of the most culturally and historically relevant illustrations of how naming and language is bound up with power and the exercise of dominance is the practice of European colonizers attacking, defiling, and altering African names in order to suppress and erase African identity. For slaves, names encompassed their identities as individuals but also aided in the survival of a collective history. Despite this erasure, one of the ways in which enslaved and free Africans sought to preserve culture and identity was through naming. In “Naming and Linguistic Africanisms in African American Culture,” Lupenga Mphande writes that, “The movement for re-naming and self-identification among African Americans started at the very dawn of American history.”

The violence with which name, identity, and colonialism is embedded with slavery is exemplified in the novel and film, Roots, wherein the protagonist Kunta Kinte seeks to retain his birth name at the expense of extreme physical and psychological abuse. First shown on television in 1977, it had a significant impact upon naming in the African American community. As Richard Moore writes in The Name ‘Negro’ — Its Origin and Evil Use, “when all is said and done, slaves and dogs are named by their masters, free [people] name themselves.”

In fact, the history of the English language has always been tied to power and patriarchy. This is most keenly illustrated in the following etymologies, tracing female-centered words back to roots which define women by their relationship to men and how they are useful:

Female: Latin, femina, meaning fetus

Lady: Old English, hlaf dige, meaning loaf kneader

Girl: Old English, gyrlgyden, meaning virgin goddess

Woman: Old English, wifman, meaning female man

Male: Latin, mascul, meaning male

Boy: German, bube, meaning boy

Man; Old English, mannian, meaning man

Words are not merely names or parts of a sentence structure; they represent a dynamic of power relations. They do not exist in a vacuum; they are connected to our relationships. How we communicate language is a social process.

In Language and Power, linguist Norman Fairclough builds upon ideas of linguistic and ideological predecessors like Mikhail Bakhtin, Louis Althusser, and Michel Foucault to assert that language is the primary medium through which social control and power is produced, maintained, and changed, and advocates for “critical language awareness.”

Fairclough writes:

“‘Critical language awareness’ is a facilitator for ‘emancipatory discourse’ . . . which challenges, breaks through, and may ultimately transform the dominant orders of discourse, as a part of the struggle of oppressed social groupings against the dominant bloc.”

Ultimately, for Fairclough, awareness of language and how it contributes to the domination or subjugation of others is the first step toward emancipation. Though language is not the only site of social control and power, it is the most immediate medium at our disposal.

The English language’s implementation as a homogenizing force and its “correct” use is intricately bound up with notions of colonialism. As bell hooks herself writes:

“Standard English is not the speech of exile. It is the language of conquest and domination; in the United States, it is the mask which hides the loss of so many tongues, all those sounds of diverse, native communities we will never hear . . . in the incorrect usage of words, in the incorrect placement of words, was a spirit of rebellion that claimed language as a site of resistance . . . We seek to make a place for intimacy. Unable to find such a place in standard English, we create the ruptured, broken, unruly speech of the vernacular . . . There, in that location, we make English do what we want it to do. We take the oppressor’s language and turn it against itself. We make our words a counter-hegemonic speech, liberating ourselves in language.”

While the history of capitalization in English is obscure, the convention itself seems to be one with no clear function. During the late 17th and 18th centuries, it was customary to emphasize most English nouns with a capital letter. Personal names and proper names were indistinct from ordinary nouns, with the ultimate decision left up to the writer. It seems that typesetters and printers found the abundance of capitalization aesthetically and economically unnecessary, so, slowly over time, common nouns began to be written in lowercase while “important” nouns were italicized and certain proper nouns were capitalized.

Indeed, the arbitrariness of the convention only underscores the absurdity of imposing it onto a person’s name. Deborah Cameron, a feminist linguist and professor of Language and Communication at Oxford University, tells me, “Whoever says, ‘But the rule is, names get upper case initials’ hasn’t really thought it through: Names are a class of words whose ‘correct’ form is whatever the name’s owner says it is.”

Therefore, imposing capitalization onto bell hooks’ name, in a cruel irony, alters her identity as an African American woman and a scholar who seeks freedom through language and its resistance. Lisa Moore, professor of English and Women’s and Gender Studies at UT Austin, bluntly explains, “To misname [bell hooks] by changing the capitalization of her name is to put racist and patriarchal values above the thoughtful decision and strategy of one of our foremost philosophers.”

Imposing capitalization onto bell hooks’ name, in a cruel irony, alters her identity. Click To TweetImposing a convention or prescriptive onto language disregards the fact of its inevitable evolution and represents an attempt to colonize it in some way. Of linguistic prescriptivism, Nicholas Subtirelu, assistant teaching professor in Applied Linguistics at Georgetown University, writes, “Within the field of linguistics (particularly sociolinguistics), prescriptivists are generally seen as looking for a rationalization for their own attitudes toward others, which might include racist or classist attitudes.” Subtirelu believes that “prescriptivism” is worth practicing, but that it should be motivated by political or moral concerns. “We should not be policing others’ language for deviance from arbitrary rules. We should be policing others’ language for the way it represents the world and others in it.” For this linguist, there is only one prescriptivist commandment: “Thou shalt not use language to harm.”

Which bring us to our current moment, one in which people are policing language for the ways in which it represents the world and the people in it, the ways in which it perpetuates or dismantles power which subjugates and dehumanizes. Some are asking for more responsible use of language while others are decrying “political correctness” gone rogue; some are irresponsibly over-policing, while others are irresponsibly sputtering; some even believe that First Amendment rights are being violated because real consequences are the result of careless and disrespectful language.

There is no “correct” language, only thoughtful and careful language. Language informed by its history. Compassionate language. Language which invites rather than excludes. Language which, most importantly, evolves. “Correct” implies there is only one way for language to be, that language is prescriptive. But language is malleable; it evolves because we are malleable and we evolve. Even the existence of the term “politically correct” and its pejorative use embody exactly the opposite of what thoughtful and generous language is about and what it seeks to accomplish.

At a time when a serious presidential candidate wields cowardly language so flippantly and disrespectfully without any regard for the people he is demeaning or emboldening, fighting my editors for spelling hooks’ name correctly felt all the more imperative. What kind of hope remains if we can’t even get the language right?

Sensitivity to language is responsibility to language, and respect for its power to call forth whatever is summoned by its use. The effects of language matter. We can start by speaking to each other by the names that we choose.