Knitting, embroidery, and other crafts can be powerful tools in the fight against fascism and the patriarchy.

Even those who’ve never attended an anti-Trump protest are likely aware of the pussy-hat phenomenon. The pink-knitted caps have quickly become the almost-official symbol of resistance against The Orange One, even making the cover of Time and The New Yorker magazines.

While some have justly questioned the hats’ inclusivity, others have seen them as a novel and playful form of protest providing a welcome break from traditional forms of activism.

But these hats aren’t as unique as you may believe. In fact, women have been using knitting and other crafts, such as sewing and embroidery, in their activism for well over 100 years. In addition to advancing progressive causes, using craft as a political tool helps to rebuke patriarchal notions of femininity. Society likes to view craft-making as the dominion of docile, domestic ladyhood — but this has never precisely been the case.

Why I Felt Excluded, Then Welcomed, At The Women’s March

Ann Rippin, a researcher at the University of Bristol in the UK, who specializes in the role of cloth in society, explains that although craft was historically used to oppress women, it also gave them a creative outlet. “Traditionally, women were taught embroidery as a way of learning ‘feminine’ characteristics,” she says.

“It taught them to follow a pattern, to be neat and docile, to be inside the home rather than out in the world. You learned embroidery to advertise your marriageability.” But, she adds, “there was no way of controlling what women were actually thinking about while they were stitching.”

In the early 20th century, the suffrage movement saw women turn their needlework skills into a tool for liberation. In the UK, the artist’s suffrage league produced around 150 embroidered banners for marching with, as well as posters and postcards.

There was no way of controlling what women were actually thinking about while they were stitching. Click To TweetOf course, this was partly due to the limited technology of the time, making textiles and needlework the easiest modes of communication. But even as technology advanced, women continued to turn craft into an effective protest tool.

Betsy Greer, an artist, activist, and writer from North Carolina, is credited with coining the word “craftivism.” She tells me she was inspired to embrace the movement after she attended a parade in Greenwich Village around 2000, and saw some people with political puppets they had made.

“They were really creative and engaging, and I could see that people were reacting positively to them,” she says. “It was a real shift for me in terms of understanding what activism was. My grandma made hats for babies at the local hospital, and I started seeing that as activism — you’re engaging in an issue and addressing inequality.”

After furthering her education on activist craft by studying the women who knitted clothing for the Allied forces in the second world war, Betsy decided to enter the fray herself. She has created a number of anti-war cross-stitch designs, and is currently working on “You Are So Very Beautiful,” a series of stitched affirmations to raise women and girls’ self-esteem.

She’s also written two books, Knitting for Good! and Craftivism: The Art of Craft and Activism. “I get a lot of emails from people telling me that it’s changed the way they look at their craft,” she explains.

“Craft has been devalued throughout history — it’s been dismissed as a hobby or something only a certain type of person does. However, I think it’s very powerful to be creating something out of nothing with your bare hands.”

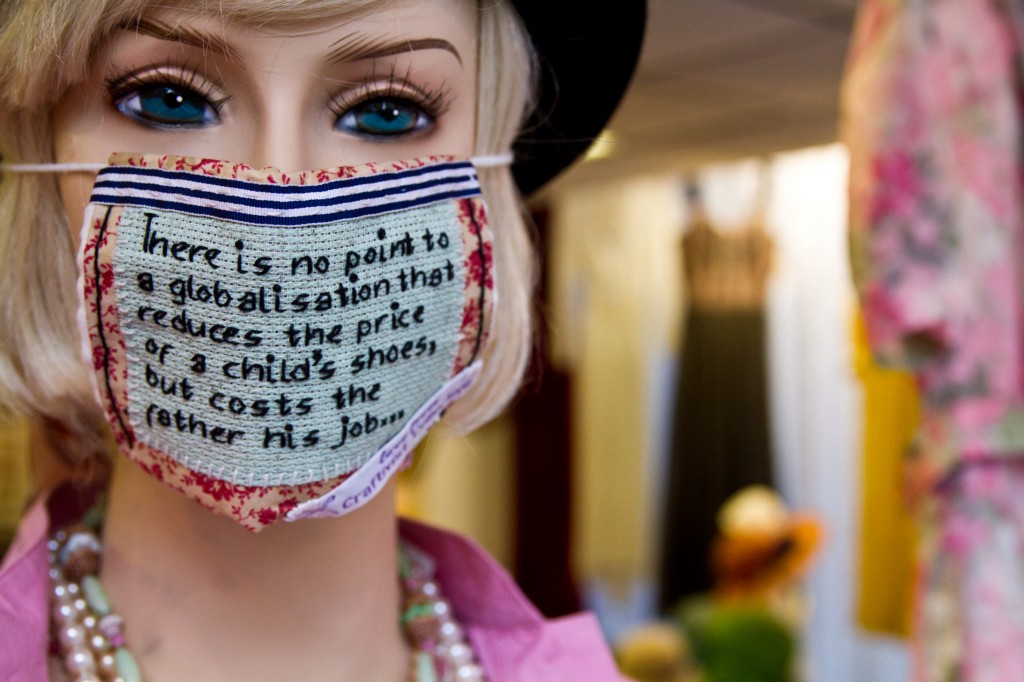

The concept has also been adopted for large-scale political campaigns. Sarah Corbett, founder of The Craftivist Collective in the UK, encourages people to create and send stitched messages to politicians addressing everything from climate change to world hunger. “In my experience, politicians really pay attention to the stitched messages they receive, because they can see that so much time and energy has gone into creating them,” she says. “They’re not used to getting handmade gifts, so they’re often more memorable than a petition or email.”

Corbett describes herself as being a “burnt-out” activist before she discovered the concept of craftivism. “It’s small, intriguing, and humble,” she says. “I also found that, when I was stitching, it would really calm me down and help me think deeply about injustice issues — what mark am I making on the world? What change do I want to see? How am I contributing to it effectively?”

Others who’ve combined craft with activism echo Corbett’s appreciation for the medium’s mindfulness. Taylor, 31, is a central member of The Yarn Mission, an organization formed after the murder of Mike Brown in Ferguson that knits for black liberation. “During the Ferguson protests, [Mission founder] CheyOnna was always knitting, and she’d stay so calm in stressful situations, such as when our space got teargassed,” explains Taylor. “I began to wonder whether it was the knitting that helped her.”

Taylor took up knitting herself in early 2015. “It became a big self-care thing for me. I’ve suffered badly from PTSD following the Ferguson protests, and I found it so calming,” she says. “I had insomnia and it helped me through the night.”

The Yarn Mission now has chapters in St. Louis, Minneapolis, and New York, and runs knitting groups as a means of creating spaces that center black women and bring communities together. “Even just organizing spaces as a black woman is so difficult because you’re dealing with both patriarchy and racism,” she says.

“But being together is healing, because dealing with racism on a daily basis is so isolating. You try to tell people what you’ve experienced, and they will dismiss it as not being real racism. It’s exhausting. So just being able to share those stories is very comforting.”

Elsewhere, graffiti knitters — or yarn bombers — use knitting to make statements about women’s place in public spaces. Yarn-wrapped trees and lampposts subvert our ideas of traditionally-masculine street art, and show how women’s craft — and therefore women — can take up space in public, rather than be shut away in the home.

In Indonesia, Knitting Gets Political

In the art world, a whole wave of women artists have incorporated crafts into their work over the years as a means of exploring issues around gender and sexuality. Hannah Hill, aka Hanecdote, has amassed a huge online following with her explicitly political and feminist stitching. “I found embroidery at 17, and really enjoyed this different form of mark-making,” she says. “Over time, and the more I learned about feminism and the sexist exclusion of textiles from the Western art world, the more it made sense for me to make socio-political statements with stitches.”

“Being half Asian, there is also a rich history of textiles in my ancestry,” she adds. “I think it’s such a powerful and historically important medium.”

Around the world, craft is also used a tool to preserve cultures and stand up against oppressive force. Hebron, in the Palestinian West Bank, was last year named the World Craft City, an honor bestowed by the World Crafts Council. Here, traditional embroidery, ceramics, and glass-blowing have become powerful symbols of preserving Palestinian identity and culture under the Israeli occupation. The Women in Hebron embroidery co-op provides women with skills and income, as well as showing steadfastness in the face of the town’s occupation.

For many women, the preservation of these skills that have been so interlinked with the female experience for hundreds of years is all part of craft’s power. “I’m using the same basic knit and purl stitches that women have always used,” says Taylor. “It’s comforting to know that I’m doing the same thing as the women who came before me, and if they could get through everything they did, then so can I.”

As for the pussy hats, they’re just the start of the battle against the current U.S. government. Already, anti-Trump embroidery is popping up on Etsy, including “Not My President” and “Real Women Fight Back” cross-stitches, and “Fuck Trump” and “Nasty Woman” embroidery. Stitched banners have also been on display at anti-Trump protests.

Activists will need abundant self-care, plus a dollop of fun and playfulness, to keep up momentum in the coming years. In other words: Grab your knitting needles.