At 8 years old, my birth name was the furthest thing from my mind. Here I was, given the God-like power of choosing my identity. It was a special kind of mask.

The internet was once a gaping void — meaningless, malleable lines of rudimentary code filled with unexplored potential. These liminal spaces between these HTML strokes were once so far removed from real life, it was as though anything said or done on the internet existed on another plane entirely. It was a veritable tabula rasa for one’s entire being; a chance to start afresh without packing up, moving to Wisconsin, and starting a free-form jazz sextet.

With time, the internet, like the viscous ooze it is, shaped itself to fill the molds and gaps of our real lives, and thus our online identities fused with our actual selves. As our virtual personae gave way to the real/virtual hybrid creatures we now know as humans, one significant artifact of the early internet was seemingly lost forever: the username.

Presently, my digital being is marked by a series of @katiefustich’s, and I can’t help but notice the increasing frequency with which my peers — particularly those in media, tech, and the arts (fields more prone to individual “branding”) — are shirking their digital aliases in favor of striking a similarly straightforward tone. True, perhaps there is the occasional number added to the end of a legal name for differentiation purposes, but even that looks oddly out of place next to the clean and simple identifiers that follow one from Twitter to Instagram and back.

![]()

The rationale behind being visible and invisible online has seemingly polarized since its inception. Now, the presence of veritable identities in online spheres consistently promotes vital conversations about identity politics. On the other hand, those who choose to remain aggressively anonymous online often do so for the more sinister purposes of engaging in cyberbullying or spewing hate speech. Yet, at one time, the username was a different kind of mask.

I was 8 years old on the first day my parents first plugged our cow-printed Gateway Computer into the phone. After a succession of aggressive beeps and whirrs emanated from the machine, I was granted the privilege of making my own AOL account. (RIP, AOL Instant Messenger.)

Selecting my user icon and away message were impossibly easy tasks (Sailor Moon and a Spongebob Squarepants quote, naturally). These things were fleeting, malleable. I could change them at the will of my American Girl doll and/or anime preferences. But when it came to fashioning my username — something so permanent, so eternally representational of me as an individual — I knew more serious considerations had to be made.

Naturally, my birth name was the furthest thing from my mind. Here I was, given the God-like power of choosing my identity, even if that identity was restricted to the AOL: Just For Kids chatroom. A username had to be witty, I thought. It had to say everything about me in as few characters as possible. It was a chance to be born again. Needless to say, the username I typed into the text box that day was none other than “RingoSpecs99.”

The username was once a different kind of mask. Click To TweetA close reading of that username reveals I, at the tender and very confused age of 8, believed Ringo Starr to be the superior member of the Beatles. I had also just been prescribed glasses and was very mistakenly excited about this life development, hence the “specs” elements (being short for “spectacles”). The 99 at the end? Naturally a shout out to the jersey number of Wayne Gretzky, the greatest hockey player of all time.

You are correct if you read that explanation as a truncated blueprint for one horribly awkward and oft-mocked elementary school student. Yet, online, it seemed okay to acknowledge elements of my personality that were — unbeknownst to me — blatantly lame. It was a safe, anonymous world where I was free to be the most distilled version of my youthful self.

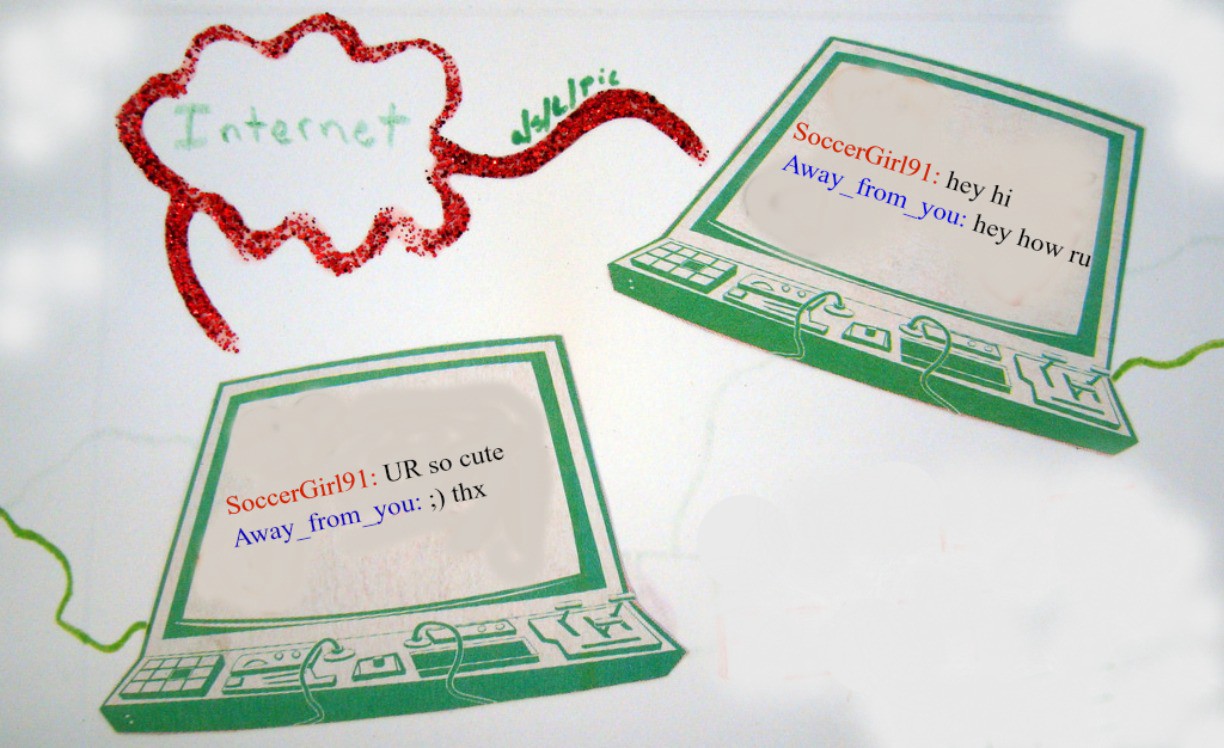

As I grew from child to adolescent, how I chose to demarcate myself virtually only became more cringe-worthy. With the birth of sites like Neopets, Livejournal, and Xanga during my gloriously goth pre-teen years came usernames like “away_from_you” (developed during a Bright Eyes listening session that lasted a fortnight), “xxguchachaxx” (a very, very deep reference from bad translations of Sailor Moon manga), and “metalmouthsweetie” (I thought getting braces meant I was cute [???]).

A few of my friends let the same username trail them from age 10 and into high school, never envisioning themselves as anything other than “SoccerGirl91” and the like. Others took a more spastic approach, creating tons of usernames due to a mixture of forgetfulness and ADHD. Yet each time a new website presented me with a blank textbox requesting a username, I felt the rush of a miniature reinvention. The endless possibilities allowed me to make who I thought I was — or at the very least, the cartoon characters I aspired to be — a more real aspect of my daily life.

Though now lampooned, these veiled versions of myself created unexpected room for growth. On sites like LiveJournal, I explored my feelings in a setting that felt safe from the judgment of my family and friends. On Deviant-Art, I offered up my rudimentary oil paintings to the surprisingly kind-hearted judgment of total strangers who were in search of similar validation. I felt like I was in on some kind of secret — while my peers in “real life” relied on the critique of exhausted teachers or confused parents, I believed I had cultivated another self in another world where people took me, a serious person, seriously. Never mind the fact that all my aforementioned real-life peers likely had similar escapist versions of themselves.

Yet not all good Will and Grace-centric FanFiction.net accounts are slated for eternity. While there’s no quantifiable moment the internet shifted from experimental space into, arguably, a vital extension of real life, there are many quantifiable reasons for the shift.

As writer and internet scholar Whitney Phillips explains to me, platforms like Facebook put indirect pressure on their users to utilize real information, and real names in particular, when crafting profiles. “If your profile name or picture is recognized as being inaccurate, your account can be deleted without warning,” Phillips explains. While Facebook promotes this pressure as “better enabling users to connect authentically,” Phillips says the site keeping its users “real” better enables them to efficiently sell this very real information to advertisers.

Zuckerberg and company aren’t the only ones in on this whole commodification of identity thing, though. Through other social media platforms, like Instagram, people have realized that if they are good enough at taking selfies or writing poetry using only leaves, they can make a living by posting the occasional sponsored ad for Detox Tea. In this scenario, the user becomes hyperreal. They’re so popular — ostensibly for being themselves — they become a kind of vessel for strangers to fill with their own desire.

For the rest of us (those unworthy of casually peddling teeth-whitening serum), we must be content to strike a balance between our true selves, and the selves we want others to believe we are. Gone are the extreme emotional torrents of my LiveJournal poetry, hello is the eternity of over-analyzing my use of internet slang in a Tweet in order to achieve an absurdly niche intellectual-comedic effect.

I say this, and yet I am admittedly disturbed when I search an individual only to find that their online identity is not in sync with their actual being. Who are they trying to fool? How do they think they could ever peel apart the two into something distinct? Humans are the internet; all we can do is articulate the way that others consume us through the medium. How could one resist the obsessive grooming of such an opportunity?

Phillips explains to me that there are many less-casual spheres in which online pseudonymity persists. “Being anonymous online is not any less common, it’s just less readily visible,” she says. It will come as no surprise to any marginalized individual that modern-day online anonymity often takes the form of hate speech, personal attacks, and associations with known violent organizations. Neo-nazi hubs like 4Chan and the Daily Stormer are littered with pseudonyms as vivid as any Club Penguin chat room circa 2006.

Shockingly, these individuals don’t make use of usernames out of shame or fear of public ousting. “Research shows that being anonymous doesn’t motivate people to be violent,” Phillips says. “It’s actually being part of a group.”

Humans *are* the internet. Click To TweetPhillips points me to the “BBC Prison Study,” a controversial project conducted by psychologists Alex Haslam and Steve Reicher that was intended to unearth new findings about power imbalances and group dynamics. Before the study, the pair of researches anticipated a correlation between anonymity and violence. Instead, the two observed it wasn’t anonymity that emboldened one to commit an act of violence, but the presence of a group. In fact, those observed were more keen on not remaining anonymous in order to receive more personal validation from others in the group, whom they hoped to impress.

Several times I have given into the temptation of crafting a new online self that is free of the restrictions of my true self online. Shortly after moving to Los Angeles, I created an alternative Instagram account, dedicated to my more base indulgences like sunset and taco photography. Though liberating at first, this sub-account quickly developed into a chore; another persona to diligently prune. The only difference in the concentrated effort placed on my two accounts was that my “fake” one was only viewed by total strangers as opposed to cute girls I wanted to be my friends in real life.

Whereas I had once yearned for the blind approval of other blank faces in the crowd, I now felt bored by their very presence. My brainwashing was irreversible — could I ever again be truly free on the internet?

![]()

The username will forever remain one of the internet’s most precious artifacts. They are today’s cave paintings at Lascaux; runes for divination by future scholars; vital pieces of an era when something that now consumes — and even controls — our lives was merely an aspect of it.

I dream of a future in which the internet becomes so all-encompassing, so separated from simply human and screen, that the username will rise again. Once more, people will choose to be anyone but themselves on the internet. Or, more accurately, be exactly who they really are.