An L.A. artist portrays workers who often exist on the fringes of society.

Most discussions around the work of Ramiro Gomez focus on his figures. It’s these bodies in space — compositional space but also public space — that make an impact.

Their presence is at turns subtle and demanding, quiet and attention-grabbing.

The faceless figures that the Los Angeles-based artist creates represent laborers; workers who often exist on the fringes of society and go unnoticed. As part of a series reflection on labor, class, and race, Gomez creates both life-size cardboard cutouts and two-dimensional pieces. The cutouts represent the quiet presence of these laborers even while they disrupt the everyday experience of passersby. A cardboard cutout of a nanny once stood near a park. Another cutout showed a man tending to the greenery outside the Beverly Hills Hotel. These often don’t last long out in public spaces — but their presence lingers.

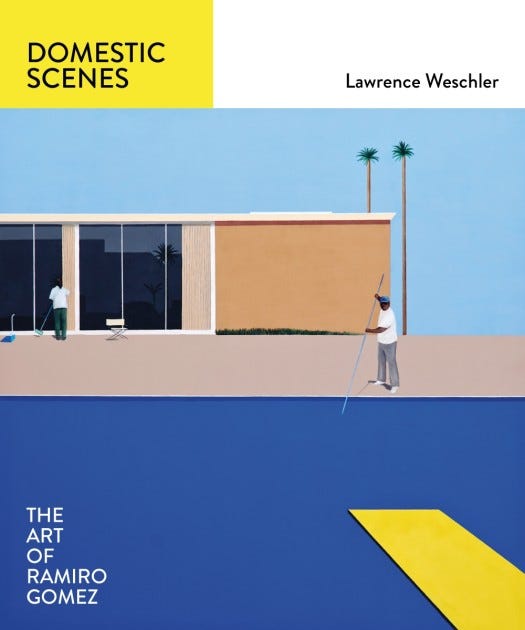

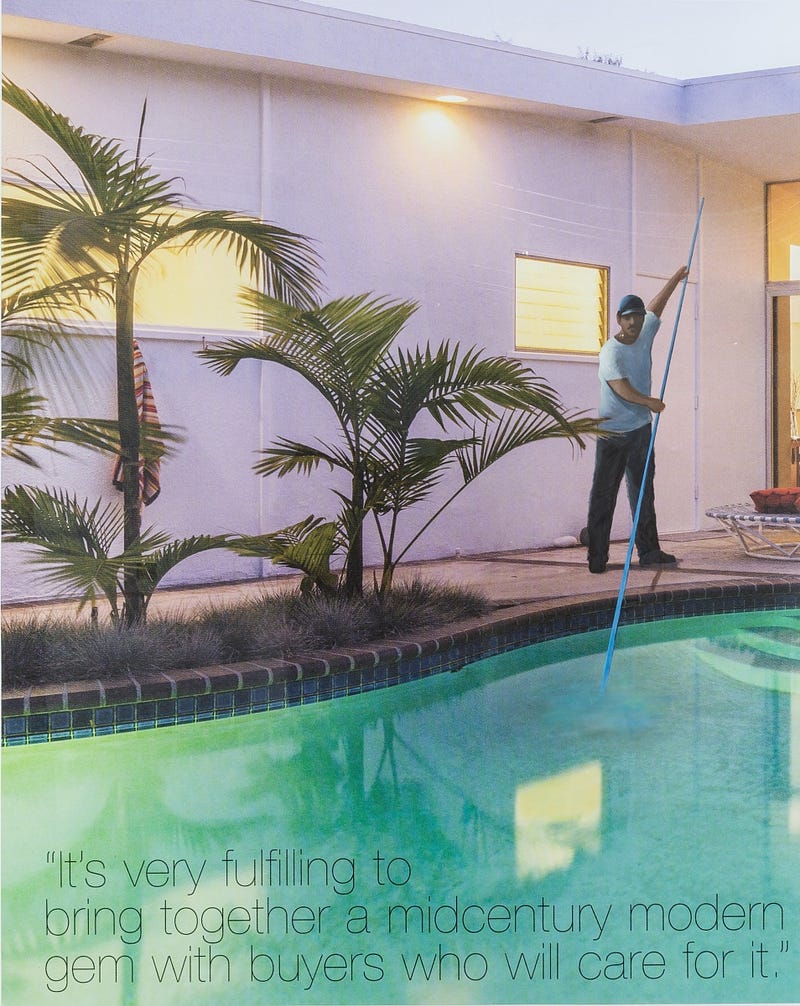

In his paintings, Gomez brings these same figures into spaces of luxury — decadent homes and modern pools that the laborers work to maintain. The artist has also gained acclaimed for placing his recognizable figures in pieces by acclaimed artist David Hockney. Formerly a live-in nanny, Gomez takes inspiration from both his own experiences and the people in his life.

Now, the artist is the subject of Domestic Scenes: The Art of Ramiro Gomez by Lawrence Weschler. The book came about after a serendipitous moment; during a Chicago visit, Weschler happened to hear about the nearby Expo Chicago art fair. Having just seen Hockney’s pieces at the Chicago Art Institute, he was surprised to find Gomez’s work riffing on that same artist. Weschler also happens to be friends with Hockney.

Weschler writes about Gomez’s work in Domestic Scenes, bringing a written component to the many forms that the artist’s work has taken. “You get a sense of how it was that it all came together,” says Gomez. “How it was that I moved from being a nanny to painting about my nanny job and then creating the magazine series that eventually leads to the cardboard cutouts that eventually leads to the Hockney series.”

The common thread that connects these pieces is those signature figures. Each scene prompts conversations surrounding labor, luxury, and race, but Gomez lets viewers come to their own conclusions.

“My tactic as an artist is simple: to just reflect it and put it out there visually for people to understand a truth that exists,” says Gomez. “Not the truth, because there is never a truth for everybody, right?”

Even while his pieces often depict iconic Los Angeles locations — and reflect a decidedly L.A. architectural and design style — Gomez has found that his figures translate to a range of cultures. As he puts it:

“I like to say that it goes beyond the American political machine, if you will, and it joins the conversation or puts it further in a universal perspective . . . My favorite thing is having a reaction from someone in Bangladesh writing back in whatever form they can, through email messages saying: ‘I really appreciate your work; it reminds me of this that I’m doing,’ or someone reaching out to me in Europe, or someone reaching out to me in South America, someone reaching out to me from Australia, the Philippines, Hong Kong — it’s so surreal that my work has reached all these other spaces.”

Gomez attributes this to a certain “contemplativeness” and “quietness” that characterize his figures and his compositions. These scenes come from a very personal place, but Gomez ultimately wants to “let everybody find answers or search for answers themselves.”

This extends to his social media presence as well. He often shares photos that depict figures in a similar way as his art. One photo shows a female worker cleaning the floor at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. Her figure is one not often seen in Instagram shots that usually focus on the art and glamorous parts of such visits.

“The way that I see museums is perhaps not how other people see them,” says Gomez. “However, as I share in social media, my eye will naturally go to those spaces. My mom’s a janitor, so if I’m in a museum, my recognition of janitors is natural. It’s also not an artistic choice. It has become that because I do paint about that, but with or without my paintings, I’m still recognizing the janitor just because I come home and I know what that janitor is like — as a mother.”

With Domestic Scenes, the artist hopes that more people can see his work — without the need to attend a museum or visit a gallery. There are few books that focus specifically on the interruption of luxury and the stark truths of labor — often art books can be seen as items of luxury themselves. But Gomez has already seen how his work impacts people from a variety of backgrounds — and how it helps generations navigate the tricky space between class identities.

For example, the artist remembers receiving a message from a student at Harvard whose mom and dad also both worked as laborers. “It’s hard to understand what that means, but your work gives me a little bit of peace,” the student shared.

For Gomez, the most satisfying part of publishing the book will be seeing it with his parents. “I will find a lot of comfort in seeing my book at my parent’s house in a coffee table, especially because of all that I’ve been through and what it means for that book to be created,” he says.