Those who can’t ‘pass’ as reasonably sane are given less agency, respect, and dignity as they navigate psychiatric care.

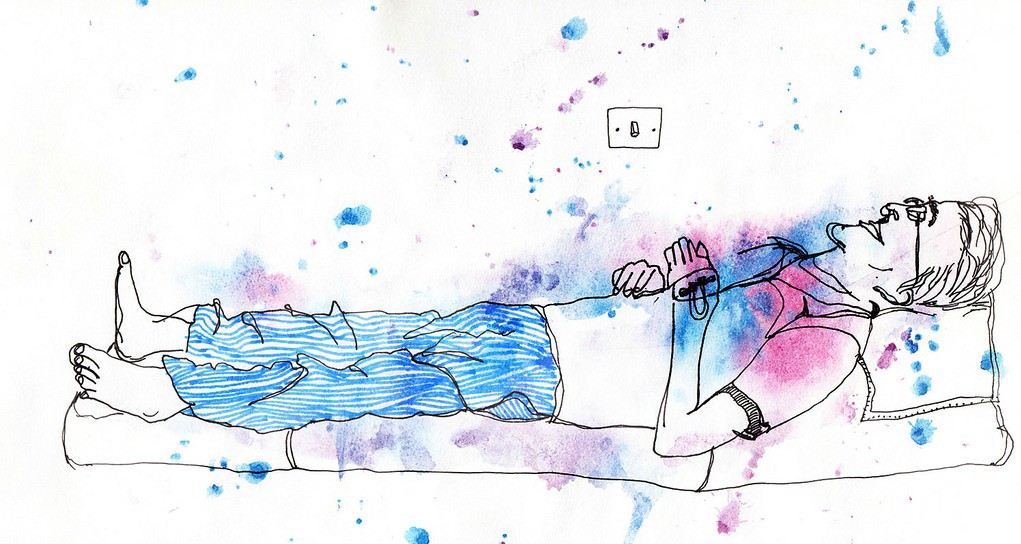

I ’m being buckled into a stretcher; restraints are being placed around my ankles when a nurse walks by.

“You don’t really have to use all the restraints,” she says to the EMT, gesturing to me with a wink. “He’s one of the good ones.”

Not like the screamer down the hall, who the nurses took up ignoring after a while. Not like the runner who tried to make a break for it past the security guard. Not like the kicker who had to be sedated after an IV mishap. Not like the cutter who tried to self-harm during the shift change.

When I was in the emergency room, I learned that if I was good, I got as many juice boxes as I wanted and Ativan — a benzodiazepine designed to help those with anxiety — every few hours. On the dot. The nurses would smile at me and bring me extra blankets; the doctors would comment on how “bright,” “articulate,” and “lucid” I was.

They liked me. They liked me because unlike the others, I was relatable, almost familiar — had we met under different circumstances, we might even be friends.

They liked me. They liked me because unlike the others, I was relatable. Click To TweetOnce a doctor even said to me, baffled, “They aren’t sending you home?” When I shook my head, he asked, “How does someone like you end up in the emergency room, anyway?”

Someone like you.

The notion of “good ones” is a lesser-known reality about mental health, as it plays out in psychiatric settings. The good ones are compliant, friendly, “higher-functioning.” And then there are the really “crazy” ones.

The ones who are too loud, too unruly, too much.

I used to try so hard to be “good.” It was something I was quite adept at. It started when I was a teenager, so ashamed of my mental illness that I did everything I could to conceal it. The charade was so successful, no one believed me when I first said I was sick.

This is what happens when you’re a people-pleaser who believes your value rests in what everyone else thinks, and that belief collides with the stigma that says mentally ill people are inherently less valuable. If they are seen for what they “really are.”

I kept it up for years. I played the role well. Too well.

I’m in the emergency room for being deeply suicidal — prompting an intervention by loved ones — and a medical doctor now immediately wants to send me back home.

The attending nurse dotes on me like I’m her long lost nephew. She offers me a special lasagna dish they don’t usually serve, she says, because she remembers that I’m vegetarian and the usual veggie option is terrible. The screamer down the hall is sobbing, “HELP, HELP, OH GOD, PLEASE HELP,” but the nurse realizes she’s forgotten my juice box, and she dashes off quickly to get it.

As if it’s the most important thing in the world. As if the only people that matter are the “good ones.”

That moment will stand out in my mind forever. It was the moment when I realized that as long as we divide mentally ill people up into “good” and “bad” — or with coded language like “high-functioning” and “low-functioning” — we replicate the oppressive hierarchies that harm all of us.

The internalized stigma that compelled me to “perform” sanity was the same stigma that can lead to neglect and abuse in psychiatric settings, and further marginalize the most vulnerable mentally ill people.

Maybe that nurse had a reason for getting the juice box instead of going two rooms down to check on the person who was screaming for help. I can never really know.

But what I do know is that these hierarchies exist — illustrated in many interactions just like that one — and my participation in that hierarchy, both to my own benefit and detriment, has very real consequences.

The internalized stigma that compelled me to 'perform' sanity was the same stigma that can lead to neglect and abuse in psychiatric settings, and further marginalize the most vulnerable mentally ill people. Click To TweetTrying to be “good” may have gotten me more blankets or special lasagna, but it says something sinister about how the stigma around mental illness operates.

Here’s what I’ve learned — and why I believe we need a more nuanced conversation about privilege and power as it shows up in mentally ill folks.

I Have (Some) Privilege Because I’m Positioned As The “Exception”

I struggle with severe mental illness and that, of course, comes with significant marginalization and strife. But because I’m so often perceived as friendly and functional, and therefore a kind of “exceptional” mentally ill person, I still benefit at the expense of other mentally ill people.

Namely, because I’m positioned as not “like them,” I am often treated better as they are simultaneously othered.

We see this kind of ableism most distinctly when we categorically divide up disabled people into “higher” and “lower” functioning — which can be a coded way of saying, “These are the people that can conform to society’s expectations of what a ‘typical’ person should be, and these are the people who fail to do that.”

I directly benefit from the ableist assumption that I am “exceptional” because I often present in the narrow way society holds up as the ideal — an ideal that expects psychiatrically disabled people to conceal their disabilities.

I directly benefit from the ableist assumption that I am ‘exceptional.’ Click To TweetIt seems to me that we want mentally ill people to not only be passive, but invisible for the comfort of neurotypical people, and especially for the ease of clinicians.

As long as I’m considered relatable, compliant, and friendly, I can expect to be treated with a lot more dignity than my other mentally ill counterparts. Kind of like the Zooey Deschanel of mental illness, where mental illness makes me brilliant and quirky — not a burden or someone to be feared or mistrusted.

And let’s be real — my success as a mentally ill writer rests heavily on the perception that I am just the “right” amount of “crazy.” The kind that inspires, the kind that allows me to give a TED Talk to a packed audience; not the kind that terrifies you while you’re on the metro because I’m talking to myself.

(But for the record? I, like most mentally ill people, have had moments of both.)

I have to acknowledge that while I do experience oppression as a mentally ill person, I am treated with more compassion, have access to more resources, and have the trust and faith of my clinicians because I can “pass” as reasonably sane in most situations.

As long as I’m considered relatable, compliant, and friendly, I can expect to be treated with a lot more dignity than my other mentally ill counterparts. Click To TweetOn the other side of the coin, the people who can’t live up to this ideal are perceived as “difficult” — often written off, misdiagnosed, or pushed off onto other clinicians — and are given less agency, respect, and dignity as they navigate psychiatric care.

Respectability politics are a real thing. And mentally ill folks are by no means immune to it.

Being Seen As ‘High-Functioning’ Can Still Be Harmful In Its Own Way

It took a long time for me to realize that being “respectable” as mentally ill hasn’t always served me.

It’s the reason that folks have reacted with disbelief when I say that my mental illnesses are severely debilitating. It’s the reason that doctors disagree about whether or not I’m dysfunctional or suicidal “enough” to be hospitalized. It’s the reason that I don’t always receive the support or care that I need, because I’m assumed to be better off than I actually am.

The first psychiatrist I ever saw said she was reluctant to prescribe any medications to me because I had good grades in school. Her words exactly: “What do you even need me for?”

We Need A Review Site For Psychiatric Hospitals — So I Built One

As a rule, before we get into the nitty-gritty of what I’ve been through, many clinicians are disarmed by my presence — some even questioning why I’m there in the first place, because I don’t “look” mentally ill.

On the whole, my treatment is a lot more competent and compassionate because I present in a way that’s more “approachable” and less “difficult,” but that doesn’t mean that I’m not presented with my own challenges.

The difference is that those challenges are still a result of stigma — namely, that mentally ill people must be dysfunctional, difficult, and unrelatable. My erasure is intrinsically bound up with the kind of ableism that ensures that “lower functioning” mentally ill folks don’t get the support that they need.

This kind of erasure ensures that I struggle to be seen as a patient, whereas other mentally ill folks struggle to be seen as human.

In other words, no one is really winning.

Being ‘Difficult’ Intersects With Other Axes Of Oppression

When we talk about who “looks” mentally ill, who presents as or is expected to be functional, who is “trustworthy,” and who is “difficult,” we can’t really ignore the fact that all of this language is situated in such a way that it plays into existing biases around race, class, gender, education, and more.

This looks like the ease with which clinicians disproportionately diagnose people of color — especially black people — with psychotic disorders, yet major depressive disorder largely goes unnoticed in these same populations due to the cultural incompetence of their clinicians.

This is why we see “difficult” women being misdiagnosed as borderline or histrionic. This is why poor folks and folks of color disproportionately wind up in prison, while white folks with class privilege (like myself) wind up in hospitals.

Who gets to be “good” and “relatable” — and conversely, who is deemed “difficult,” “crazy,” or “bad” — becomes very apparent when you take a look at who holds the most privilege and power in society.

Mental illness can and often is weaponized against the most marginalized among us, and undeniably impacts the kind of care we receive.

When I walk into an appointment with a clinician, I’m not considered “threatening” — that ER nurse can treat me like her queer little nephew because she could easily imagine that I was. It wasn’t just about how I behaved, but how I was perceived.

And when you are a college-educated, transmasculine white person, you are given the benefit of all different axes of privilege, in which people are conditioned to believe in your inherent goodness, empathy, safety, and intelligence.

Who gets to be ‘good’ and ‘relatable’ — and conversely, who is deemed ‘difficult,’ ‘crazy,’ or ‘bad’— becomes very apparent when you take a look at who holds the most privilege and power in society. Click To TweetWhen I was placed in the ambulance the first time I was committed, the EMT told me he’d unhook my restraints — just seconds after putting me in the ambulance — because “I probably wouldn’t punch him.”

In a single loaded statement, I was acutely aware of the fact that my perceived “safety” had everything to do with his immediate impression of me — and nothing to do with how mentally ill or unsafe I might actually be.

Much of mental health care has to do with quick assessments and judgment calls. But who gets the benefit of the doubt — and how patients are ultimately categorized, diagnosed, and cared for — can be deeply impacted by existing prejudice.

And because of that, my experiences as a mentally ill person will always be shaped by the hierarchies that exist both within this community, as well as the ones systematically designed and enforced outside of it.

I’m seen as “one of the good ones.” But that’s due, in large part, to the privileges I already have.

My experiences as a mentally ill person will always be shaped by hierarchies. Click To TweetSo no, I no longer revel in being seen as the “exception” — sipping on a juice box, propped up by an extra pillow — looking for the approval of my clinicians and nurses.

I don’t delight in being anybody’s “favorite patient,” as flattering as that might seem.

I recognize my perceived “goodness” for what it actually is: Undeniably harmful, bound up in somebody else’s oppression.