Cognitive disability is typically decorative in the horror genre—a surface on which to project our fears—but ‘Hereditary’ is one of the first horror films to complicate that narrative.

Warning: there be some spoilers ahead!

For me, the most haunting image of disability ever depicted in a horror film is a sequence in Stuart Gordon’s From Beyond (adapted from H.P. Lovecraft’s short story). A woman peers at the inmates of a psychiatric institution through the tiny windows of their rooms, their aggressive performances of mania framed like paintings in a gallery. The imagery sticks with me for its tidy encapsulation of the attitude toward cognitive disability in the horror film.

Cognitive disability — specifically, a stylized form of cognitive disability that I will refer to as madness — is decorative in the horror film, a surface on which to project our fears. Unfortunately, this particular depiction of madness serves as little more than a colorful, sensational accoutrement, reducing disability to a storytelling or stylistic device, playing into a medical model of disability that reduces its complexity into a series of external expressions to be controlled and eliminated.

Ari Aster’s excellent film Hereditary risks the same fate and interpretation.

On the surface, Hereditary appears to be a film in which disability constitutes a prop in a play of terror, only to be overwritten and forgotten in the presence of overwhelming supernatural explanation. But to ignore the role of real mental illness in Hereditary would be to miss a salient facet of the disabled experience and the role of mental illness in horror cinema.

Terminology is important here, because different terms imply different models: I use “mental illness” deliberately because that is, I think, the lens of certain characters in the film, and it seems the most apt term to describe Annie’s relationship to the idea of cognitive disability, which dominates the early film.

To ignore the role of real mental illness in Hereditary would be to miss a salient facet of the disabled experience and the role of mental illness in horror cinema. Click To TweetWhen Annie lays out her family history, she uses clinical terms to describe her family members’ various mental states — psychotic depression, schizophrenia, etc. — in a subdued scene that minimizes sensationalism and emphasizes Annie’s process of medicalizing, rationalizing, and therefore managing her family according to one of the most prominent models of disability.

Tobin Siebers, noted professor and disability scholar, usefully lays out the two major models of disability: “the medical model defines disability as a property of the individual body that requires medical intervention,” while “[t]he social model opposes the medical model by defining disability relative to the social and built environment.”

Siebers suggests that “the next step is to develop a theory of complex embodiment that values disability as a form of human variance.” Hereditarydramatizes a shift from the medical model — e.g. Annie’s representation of her family — to a model of complex embodiment exemplified by the film’s ending.

Disability theorist Robert McRuer suggests there is a transient nature to disability in the dominant cultural imaginary: “According to the flexible logic of neoliberalism, all varieties of queerness — and, for that matter, all disabilities — are essentially temporary, appearing only when, and as long as, they are necessary”; this may be enacted through the “miraculous cure,” as Martin Norden calls it, or through disavowal of a disability that was never really there in the first place.

Take the third Nightmare on Elm Street film, Dream Warriors, which is centered on teens incarcerated in a psychiatric facility. The terror the teenagers feel for the murderous Freddy Krueger— who hunts them in their dreams — is mistaken for mental illness, and the children must battle the staff whose misconceptions could (and sometimes do) prove fatal to them.

Dream Warriors encapsulates the ways that disability functions as a veil to be discarded and a label to be rejected: The protagonists aren’t actually “crazy,” not like those people — namely, the “hundred maniacs” said to have fathered Freddy Krueger. If Hereditary at first appears to be just such a film — in which disability appears early and is later discarded — closer readings reveal it to be a much more nuanced take on disability.

Where so many horror films use disability as a cover for or diversion from the supernatural, Hereditary is both part of a tradition of films that use horror to explore mental illness as lived phenomenon and part of a recent wave of body horror films that redefine the imagery of the genre.

Mental illness in horror is madness; not madness in the way that the word has been re-appropriated by, for example, a variety of groups and movements that have used the moniker “Mad Pride” in celebration of mental illness, but in the (arguably related) sensational, exploitative sense, preceding scientist or doctor: madness as the horrorization of disability.

Madness is a cloak in horror cinema: It drapes its subject in meaning; it’s an easy shorthand for a medium whose mantra is show, don’t tell. The villain is mad: dangerous, unpredictable, shattering the boundaries of acceptable behavior. Whether in the tradition of tinkerers like Dr. Frankenstein or killers like Norman Bates, mental illness is stylized into madness (or perhaps the reverse: style goes mad) and then violence is projected onto it.

'Hereditary' is both part of a tradition of films that use horror to explore mental illness as lived phenomenon and part of a recent wave of body horror films that redefine the imagery of the genre. Click To TweetIt is a well-worn truth that mentally ill people are more likely to be the victims of violence than to inflict it themselves, but the problem with the “madman” trope is as much in its hollowness as in its inaccuracy: It is all surface and no depth, fleeting and ephemeral. However, there is another strain of horror, which I’ll call mad horror, that explores madness in a different way: namely, as an experience, a “complex embodiment” in which a person lives.

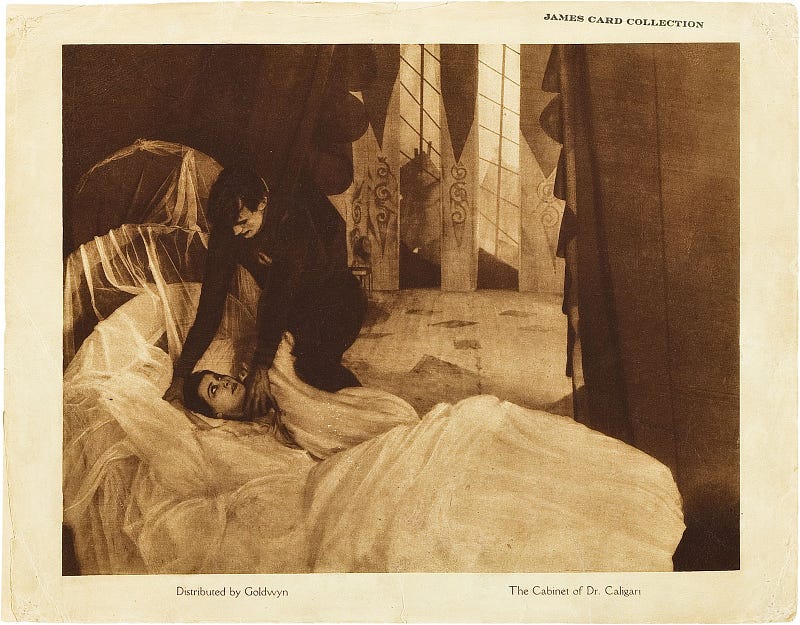

Mad horror cinema can be traced at least back to The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari(1920), in which the exaggerated, subjective sets that have come to define German Expressionist cinema are the representations of a mind in the throes of madness.

Caligari, through its use of exaggerated, counter-realistic design, narrates the process of rendering mental illness into madness; it is the process of, in Siegfried Kracauer’s words, the “transformation of material objects into emotional ornaments,” the visualization of the ostensibly invisible. Caligarihelped set a precedent in horror for the visualization of cognitive disability in everything from cinematography and lighting to physical sets and props (since Caligari, sound cinema has allowed for the use of sound effects to signify madness as well).

The projection of madness into the physical environment of Caligari is echoed in Hereditary through Annie’s hyperrealistic miniatures and her daughter Charlie’s grotesque dolls. If Annie’s gallery of perfectly lifelike imitations reflects her attempt to maintain sanity in her family, Charlie’s suggests an abnormal mind that foreshadows an alternate reading of the film.

As much as it is the story of a coven of witches conspiring to place the spirit of Charlie (who was really a king of hell all along, or something) into Annie’s son Peter’s body, Hereditary may also be Peter’s slow break from reality, probably triggered when Peter accidentally kills Charlie. From this standpoint, it makes sense that Peter would symbolically resurrect Charlie the only way he can: within his own body.

Peter’s descent into madness echoes mad horror films like Repulsion and more recently films like Black Swan and Darling: films that explore mental illness as a lived, physical experience, in which the horror is derived from one’s mental state. Hereditary — in presenting multiple possible readings — is a film that revels in the slippages between psychosis and the supernatural and the indeterminate nature of that boundary.

The line between those two phenomena has always been tenuous in the horror genre, but Hereditary takes that boundary as its secret subject. Before Hereditary, David Cronenberg’s Videodrome more overtly explored the same slippage between reality and hallucination. “There is nothing real outside our perception of reality,” Brian O’Blivion tells Max Renn, suggesting that reality is just one shared hallucination.

Hereditary follows in Videodrome’s footsteps both by exploring madness as something lived rather than merely seen and by disrupting the line between the real and the unreal and that between body and mind.

In his book Crip Theory, Robert McRuer argues that:

“[a] system of compulsory able-bodiedness repeatedly demands that people with disabilities embody for others an affirmative answer to the unspoken question, ‘Yes, but in the end, wouldn’t you rather be more like me?’”

McRuer, by contrast, proposes the radical possibility of taking pleasure in disability, that “disability and queerness are desirable.” (McRuer’s focus on queerness — in addition to disability — is actually quite relevant to a film centrally concerned with the breakdown of a traditional nuclear family unit.) This desirability is central to Cronenbergian body horror, particularly the oeuvres of Cronenberg and Clive Barker.

Hereditary — along with recent films like The Neon Demon, The Lure, and Get Out — is a kind of post-Cronenbergian body horror focused less on dramatizing transformation visually on the body, but rather on redefining the relationship between self and body and between body and image.

Less sadomasochistic than their predecessors, post-Cronenbergian body horror (which actually may be said to begin, ironically, as far back as Cronenberg’s own Dead Ringers) focuses less on pleasure and more on the uses and abuses of the (literal and metaphorical) social body, like the dehumanizing cult of female beauty in The Neon Demon.

Hereditary explores not only the mad body but the familial body, specifically that of the nuclear family, whose supposed safety and stability — signified by Annie’s rigorous models — is seen to be, in reality, tenuous at best (while the models themselves comment on the constructedness of the nuclear family). That the film ends on a coven chanting around Peter at the coronation suggests that the conventional family has given way to a non-conventional family just as Peter has entered a non-conventional mental state. As in Hereditary’s predecessors, this ending may not be undesirable to those actually experiencing it.

'Hereditary' explores not only the mad body but the familial body, specifically that of the nuclear family, whose supposed safety and stability is seen to be, in reality, tenuous at best. Click To TweetLike Caligari, Hereditary has a frame of sorts, opening on a pan through a room full of miniatures before settling on a model of Peter sleeping in his bed, from which the action seamlessly begins. By framing the entire film as, quite possibly, an exhibit of Annie’s art, the film blurs the line of narrators: is the film Peter’s, or in opening on Annie’s model of Peter, is the film Annie’s?

Hereditary is a familial intermingling of consciousnesses — Annie’s, Charlie’s, Peter’s — that defies representations of mental illness as surface level stylization or as a problem in need of a cure and in doing so, resists the stigmatization of disability so prominent and dangerous in the horror genre. Despite a fraught and complicated history, the horror model of disability can offer a surprisingly nuanced and empowering way of looking at the experience of madness.