I was in my early twenties when I first joined Fight Club. I’d recently started watching mixed martial arts championships on TV, and I was intrigued. I fell in with a group of similarly curious and equally untrained women, and together, we started attending a martial arts and MMA club that was held in a local circus collective’s warehouse space on Thursday nights.

Our fight club had little in common with Chuck Palahniuk’s vision. No one really talked about it, but that was more due to its lackluster marketing efforts than rules. Our band of women had little contact, physical or verbal, with the rest of the people in the warehouse. We mostly kept to ourselves and “wrestled” using whatever combination of moves we’d managed to pick up from self-defense seminars and a lifetime of watching action movies or WWE. But there was usually an air of confused and frustrated masculinity lingering on the worn mats as a group of random men practiced their best Aikido moves nearby.

Most of those men ignored us. Some of them regarded us with a contempt that they concealed about as well as they concealed their surreptitious flexing in the floor-length mirrors that lined the space. One kindly showed us random techniques, including a wrist lock defense “in case some guy grabs you.”

I was giddy with excitement over my new hobby, the possibilities of learning new technique running wilder than Hulkamania through my head. But almost immediately, when my muscles were still stiff from my first attempts at break falls, I started having to field puzzled questions. When I tried to explain this exciting new development in my life to casual acquaintances, friends, and family members, they’d respond with some variation of: You’re so little/sweet/smart/gentle/cultured. Why would you enjoy something so violent?

I didn’t know how to answer them. I wasn’t entirely sure that I understood the question at all. It was hard to associate what I’d done with my friends with my concept of violence. Yes, I’d been aware that there was a risk of injury inherent in everything that we’d tried at the gym, but I didn’t feel like I was in any true danger when I was sparring with my friends. I felt relatively safe in that gym. I trusted that no one around me truly wanted to hurt me and that I didn’t have to fear their actions. Which was more than I could say for the walks home after Fight Club in the middle of the night.

I led a relatively sheltered and privileged childhood, but I was still quite young when I first realized that there were other people who might want to hurt me. I was 10, it was the spring of 1992, and two teenage girls named Leslie Mahaffy and Kristen French had been kidnapped and murdered not far from where I lived. At school and at home, little girls like me were warned about the danger lurking in our own backyard and told to watch out for a man driving a cream Camaro.

This is also when I first started fantasizing about kicking ass. I was vigilant and paranoid, holding my breath when I passed any light-colored car and going over and over what I’d do to the man if he tried to pull me into his vehicle. While the boys I played with pretended that they were the Karate Kid, or even my beloved Ninja Turtles, I just wanted to be the girl that got away.

That winter, Paul Bernardo was arrested. Besides Mahaffy and French, he had killed at least one other young girl and raped at least 13.

Violence was already a presence in my life, whether I wanted it there or not. The only choice I had in the matter was how I wanted to interact with what was already there and what would probably remain there for the rest of my life.

My first instinct was to try to arm myself. I was being told, both directly and indirectly, that I needed to be able to defend myself, that I had to develop and maintain the skills that could prevent others from hurting me, so I dutifully signed up for the first self-defense sessions that I could find. The lessons were effective enough — although, as blogger Kitsutoshi expertly lays out in her post “Martial Arts delusion and how it hurts women,” any self-defense program that primarily focuses on one’s ability to fight off a stranger in a dark alley leaves most women woefully underprepared for the kind of danger they’re most likely to face in reality. But they were ultimately unsatisfying. I was left with a random collection of skills that I hoped I’d never have to test in real life.

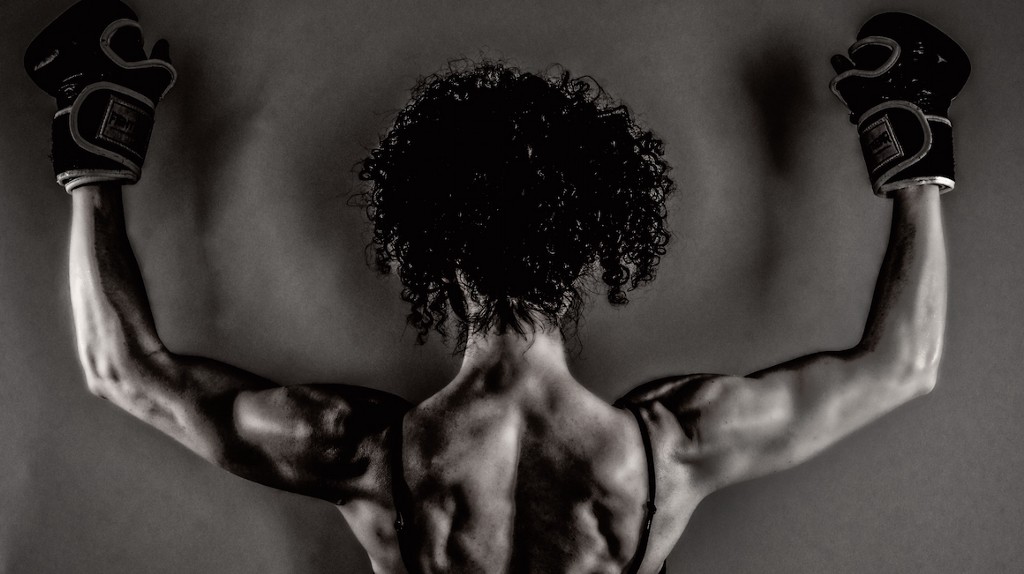

It wasn’t until I joined my weird little Fight Club and subsequently found myself on the fringes of the mixed martial arts community that I finally found the outlet I was looking for. Fighting — and watching fights — also allowed me, for the first time, to play with the skills that I’d learned, and to have some say in how I could interact with physical force. I was able to take the knowledge that I’d gained and apply it in a safe and controlled environment where I could be more than prey literally fighting for my life.

There’s a whole sub-genre of martial arts films, like The Karate Kid, dedicated to beleaguered young people discovering a discipline, standing up to bullies, and achieving glory. The narrative plays out in real life, too; combat sports, particularly boxing, have provided both an outlet and calling for generations of underprivileged fighters. But these origin stories usually center around boys, surrounded either by urban violence or bullying. We don’t talk about the women who turn to formalized, structured fighting as a respite from the chaotic threat we face every day.

That’s an especially unusual story in MMA, and MMA-adjacent training in disciplines like Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu, Muay Thai, and wrestling. These forms of fighting are more associated with narratives about unleashing violence than harnessing it — and specifically, men unleashing the violence that is their innate masculine birthright. It’s often seen as an escape from a civilized and complacent society, the one place where emasculated modern men can reclaim some sort of long-lost rush of primal aggression both as fighters and viewers.

Before North American WMMA pioneer Gina Carano started attracting attention, women in mixed martial arts were acknowledged only by the community’s most dedicated disciples, and even then their motives were often misunderstood. More often than not, these female competitors and fans were dismissed as outliers who either wanted to impress boys or ruin their fun. We might be tomboys, or Not Like Other Girls, or maybe we had some scary feminist agenda. But few were open to the idea that we were there for reasons that were outside of their own experiences or knowledge.

Every single woman I’ve ever met through training, watching, and now writing about martial arts has had her own origin story as individual as she was, but we all had one thing in common: None of us had turned our backs on a safe and innocent paradise of pacifism to embrace a life of wanton violence. The violence had been in our lives all along.

The next five years of my life were an ongoing variation on these themes. I left the fight club women to join an all-female professional pillow fighting league, where I engaged in mostly unskilled and barely-regulated MMA-style matches — with pillows! — for tiny sums of money and even tinier traces of glory. I joined a Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu gym to become a better pillow fighter, and then I quit bedding-based martial arts entirely so that I could take my BJJ training more seriously. I attended a class run by a brilliant female black belt from Brazil who spent 30 minutes teaching us what to do if a police officer chokes you at a bar. (“You say ‘Not Guilty!’” she laughed, throwing her hands up. Then she showed us how to snap a pinkie finger backward.) I took up Muay Thai and the occasional MMA class, jokingly dubbed my fists “Mary Kate” (left) and “Ashley” (right), and learned to throw one of the meaner Ashleys at the gym. I received both praise and warnings for my efforts. “You’ll break that if you try to hit a guy who’s attacking you,” one instructor warned as he pointed to my tiny fist. “Use your elbows instead.”

People from the outside world continued to wonder what the hell I was doing, I tried various explanations out on them the way I’d test newly learned submissions: It was good for fitness. It was great for stress relief. There were worse ways to meet new people. If I was feeling particularly whimsical, I’d joke that I’d always wanted to be a Ninja Turtle (preferably Michelangelo) or Emma Peel. All of which were true, but none of which were really convincing to other people or satisfying to me on their own.

I wasn’t even convinced that what I was doing was actually violent. Yes, I regularly came home from the gym with black eyes and bruises in the impression of my training partners’ fingers all my limbs. I even broke one of my toes at a grappling tournament, although that was the result of me running tarsal-first into a giant man during warm-ups as opposed to an actual in-combat injury. But I didn’t consider any of that any more brutal than anything that could have happened to me — or that I could have inflicted on someone else — during any other athletic activity. My opponents and I were trying to win, not hurt or kill each other. I never felt scared or threatened when I was fighting them. Any time I was remotely hurt, overwhelmed, or overpowered, I could make it all stop immediately with a couple of light taps in submission.

It was physical. It was intense. But at no point on the mats did I ever feel like I had to be wary of the people around me. No one dared to touch me without my clearly indicated consent. And, if they had, it would never have been excused in any way.

When I stepped off the mats (or out of the ring or cage), I still lived the same way I always had: on alert, carefully guarding my drinks, walking with keys threaded between my fingers, hoping that I could trust my instincts, my training, and my reflexes if circumstances ever required them. Hoping that one wrong move couldn’t cost me my life. To me, that was violence. What I did on the mats was fun.

Mixed martial arts may have have been a Thunderdome-like “human cockfighting” free-for-all when it first made such a polarizing impression on the public consciousness in the early 1990s with the first Ultimate Fighting Championship PPVs, but in its current form it’s a complex and highly-regulated sport filled with dedicated athletes who are masters of multiple disciplines. And while the culture surrounding the sport is still not entirely safe — and, in some cases, not entirely welcoming — for anyone who’s not a cis male, the training and the fights themselves can offer a welcome alternative to the violence that surrounds us in real life.

When I fight, or when I watch fighting, I’m indulging a rare opportunity to dictate the terms on which I engage with violence. However briefly, I can take something that has been an ongoing source of fear, frustration, and genuine danger, and turn it into something that I can enjoy. Something I have some control over. Something that, when I actually bother to train properly, I can actually do well. I’m not sure that I’d go so far as to declare the experience liberating or empowering, but it certainly is refreshing.

For the men who hail martial arts in general and MMA in particular as a gloriously barbaric return to a time of brute strength, honor, and the alpha male, I can image that the sport does offer an exciting alternative to a world that they believe is too safe and sanitized. But as someone who doesn’t have the privilege of living in a world with so little risk and so little threat, two evenly-matched, consenting adults who engage in bouts with clear rules, regulations, and supports represents a different idealistic fantasy. It’s a fantasy that’s often missing from my own life: a fair fight.