When it comes to social progress, shame is proven to be an effective tool.

By Aja Barber

Contrary to increasingly and troublingly popular belief, your racist relatives on Facebook aren’t funny. They’re racists, which means they probably think less of people who look like me. So why do so many people insist on treating family members who say heinous things as harmless or even borderline-endearing?

Casual, blithe mentions about that “crazy racist aunt (or uncle)” are getting thrown around so much, it’s starting to feel like white people collectively consider racism a lighthearted joke. As if having a racist relative is just “one of those things,” like a run in your tights or a partner who never picks up after themselves. As if the racist relative isn’t actually that big a problem, because you feel untouched by their problematic views.

Just recently, a website I occasionally read featured a pop-up declaring that you should “like” them on Facebook, because they do social media just like your racist aunt! If you identify and chuckle at that “joke,” you should feel ashamed of yourself — because it’s not funny. But mostly you should feel ashamed because it definitely means you haven’t stood up enough.

And yes, I know the question that’s going to be asked now: Have I stood up to my own problematic relatives online? And my answer is: Of course I have. I don’t get to pick my coworkers, and when it comes to holiday dinners, I don’t really get to pick who I break bread with. But in my online space, I get to say who comes in and who stays out. And I’ve decided that racists and other assorted bigots always belong in the latter camp.

It’s starting to feel like white people collectively consider racism a lighthearted joke.

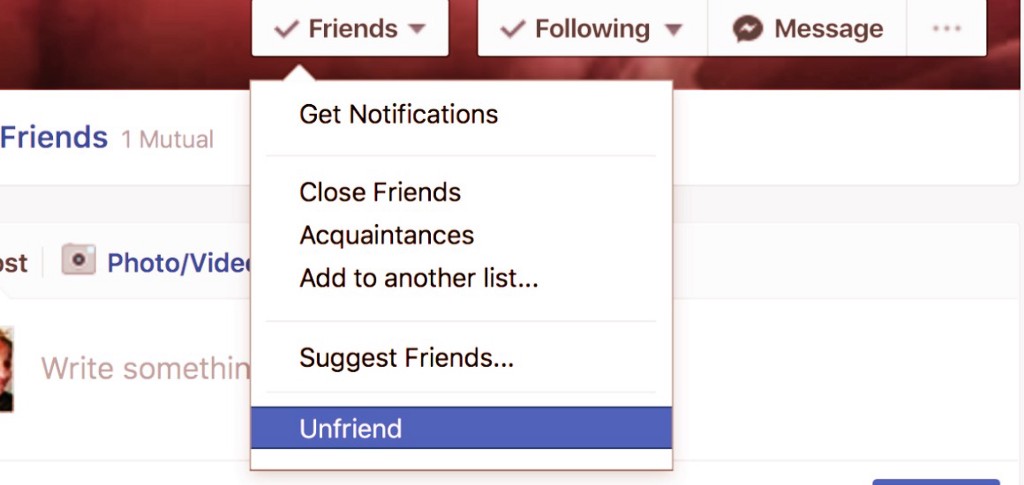

Someone I know, for instance, was always writing problematic posts and sending troubling messages to me about women on Facebook. Because I know these sorts of patriarchal, oppressive ideas are deeply held, I decided that wasting my sweet precious afternoon trying to educate them and their ignorant friends for the greater good of women everywhere wouldn’t be an efficient use of my time. So instead of engaging with them, I deleted them and kept on trucking. Now, not only do I not have to deal with their sexism, but I also no longer receive transphobic jokes in my inbox. Two birds, one stone.

Unfriending racists has had wider-reaching consequences than just protecting me. Sidelining people who spout off damaging views also spares my other Facebook friends, as there are a number of ways that racist relatives hurt and offend. From jumping ignorance-first into comment threads on my posts, to adding remarks — and sometimes attacks — to the posts well-meaning friends leave on my wall, bigots have many methods of spewing hate.

Friendship In The Age Of Unfriending

So, when you unfriend someone, you are not only protecting yourself, but others too from their vile “opinions.” Moreover, by making the active choice to block them from your online space, you are also sending a very loud message: I don’t want you hanging around me with those views. Yes, feelings get hurt. But whose feelings would you rather have hurt? Your unassuming friend of color? The person whose humanity is being stripped away by a diatribe about the “race card”?

Or that racist aunt you barely tolerate who makes you cringe when she talks loudly in public about “illegals”?

The fact is, when it comes to social progress, shame is proven to be an effective tool. When I grew up in Virginia in the ’90s, for instance, homophobic rhetoric was still somewhat acceptable. Now, if you utter something homophobic in public, you should probably expect to get a dressing down, and rightfully so. Of course homophobia still exists in our society, but it’s generally become very unpopular (unlike, say, transphobia, which still despicably gets a pass). Pop culture, marriage equality, and a myriad of other cultural shifts in our society have contributed to a change in views about homosexuality — but so too has the simple fact that at some point, people began telling homophobes that they wouldn’t tolerate their hate. Humiliation is an effective way to make people take note of their problematic views; it may make them uncomfortable, but that’s kind of the point.

Remember, too, that when you unfriend a racist relative, you’re doing your small part to stop the very real issue of Internet harassment. Ask a vocal, marginalized human being how many times a day they receive abuse or harassment on the Internet — the answers will probably surprise you. You putting your foot down is you doing your part to stop that. Maybe racist auntie or uncle will think twice before they harass an innocent stranger from the safety of their computer screen, for fear that others will also swim away from them like a turd in the pool. Maybe not. But it’s well worth a try, isn’t it?

I understand that all those people who choose not to take a stand against their racist relatives on Facebook are afraid of being ostracized by other family members. But as someone who has a long history of unfriending people (quite happily, I must admit), I’m here to tell you that at the end of the day, everyone always gets over it. I’ve never apologized or added anyone back until they learn from the experience . . . and they always do. Maybe there are glib comments here and there made about me, but ask me if I care. (Spoiler alert: I don’t.)

And even if they don’t get over it, I’ve decided that at the end of the day, the humanity of those who’ve been offended by hurtful remarks is way more important than bigots feeling hurt because certain spaces of MINE (that’s right, MINE) are no longer accessible to them.

When you unfriend a racist relative, you’re doing your small part to stop the very real issue of Internet harassment.

Everyone has problematic relatives — but keeping them around isn’t mandatory. Sure, unfriending them is messy. It’s not fun at all. But you know what your passive disapproval is at the end of the day? It’s a pass. And when enough passes are handed out, the implicit message is that racism really isn’t such a big deal.

And for the record, because this happens a lot, I don’t hand out brownie points if — after swallowing your tongue when a relative says something you know to be racist in a comment thread I see — you tell me in a private message that you “disagree” with their opinions. Whether you message me to apologize in private or not, you’re still letting someone get away with problematic behavior. You’re also putting the burden on me, unloading your racist problem like a cat delivering a dead bird to my feet. (Emotional dumping about racism to your friends of color is an entirely different essay in itself.) My day has been thoroughly ruined by racism a great many times in my life. I’d prefer to get a little less of it delivered straight to my inbox by well-meaning friends who can’t reconcile the behavior of a blood relative who they choose to allow in their online life.

So the next time your racist tea partier relative decides to chime in on an otherwise pleasant but topical discussion, please, for the love of God, don’t message me privately about it. You have free will. You don’t need my permission to unfriend them. You shouldn’t even need my encouragement. Just unfriend them. With reckless abandon.

And if you remain inactive one too many times, don’t be surprised if I unfriend you.

Looking For A Comments Section? We Don’t Have One.