“If we don’t have the words we cannot understand what the vulva is or how it looks and works.”

What do you call your private parts, to yourself, to your doctor, in polite company? There are plenty of slang words for the female genitalia—some cute, some raunchy, some silly, some banal—but none of them, not even the scientific-sounding vagina, is quite right.

The term vagina refers to the canal that connects the inner, non-visible organs—cervix, uterus, ovaries—to the visible, outer part, which is the vulva. Often, when we refer to our pussy, hoo-haw, cooter, or vagina, we’re actually talking about is our vulva. Given that “vagina” isn’t —arguably— the prettiest or most exciting word out there, why is that our collective, patriarchal culture insists on using it?

Swedish artist Liv Strömquist wants women to reclaim the word vulva. Or, more specifically, she wants us to—finally—claim it. The illustrator, whose book of graphic nonfiction, Fruit of Knowledge: The Vulva vs the Patriarchy, was released in English last month, aims to destigmatize the female body, especially the vulva, the orgasm, and menstruation.

The 40-year-old feminist activist felt a lot of shame about her body growing up, especially when it came to menstruation. As an adult, she decided to start looking into the taboos associated with the female body. She started asking pointed questions, like, “Where does the taboo around the vulva come from? Has it always looked the same throughout history? How does the taboo around the vulva affect us women psychologically?” she told me via email in early October. “All these things were very interesting for me. I wanted to investigate why there is so much shame surrounding women’s bodies—and in particular the genital parts—in order to change it.”

The 40-year-old feminist activist felt a lot of shame about her body growing up, especially when it came to menstruation. As an adult, she decided to start looking into the taboos associated with the female body. She started asking pointed questions, like, “Where does the taboo around the vulva come from? Has it always looked the same throughout history? How does the taboo around the vulva affect us women psychologically?” she told me via email in early October. “All these things were very interesting for me. I wanted to investigate why there is so much shame surrounding women’s bodies—and in particular the genital parts—in order to change it.”

And then, in 2012, she started turning what she had discovered into Fruit of Knowledge (originally published in Swedish in 2014 as Kunskapens frukt), a cultural history that explores—in edgy, satirical tones and comic-book form—the pathologies, politics, and oft horrifying punishments that female and trans bodies have suffered at the hands of religion, science, and men.

The meticulously researched Fruit of Knowledge chronicles—toggling between dead serious and drop-dead funny tones—the female body’s mistreatment and mishandling, starting with Eve and winding through history, medicine, pop culture, sex ed, contemporary advertisements, and more.

As graphic nonfiction gains more of a foothold in the literary world, we see more and more serious subjects conveyed in comics form. Here it brings awesome power to a misunderstood and hushed-up topic.

Where does the taboo around the vulva come from? Has it always looked the same throughout history? Click To Tweet“So much is communicated with a well-drawn side-eye, angry eyebrows, etc.,” translator Melissa Bowers told me via email. “The first time I read [Fruit of Knowledge] I was either giggling, cringing, or both. I was so charmed by Liv’s simple, expressive drawing style.” Charmed is a surprisingly accurate response to the way Strömquist conveys information. When asked why she chose the comics form to write about such thorny material, she said, “I’ve always really liked comics, since I was a child. If you see a comic in a magazine you immediately want to read it—and this is why I really like this art form. It’s very appealing, not difficult or pretentious. It’s folksy. Articles about feminism and left-wing politics often tend to be very heavy, academic and serious, so I like to make my work fun to read.”

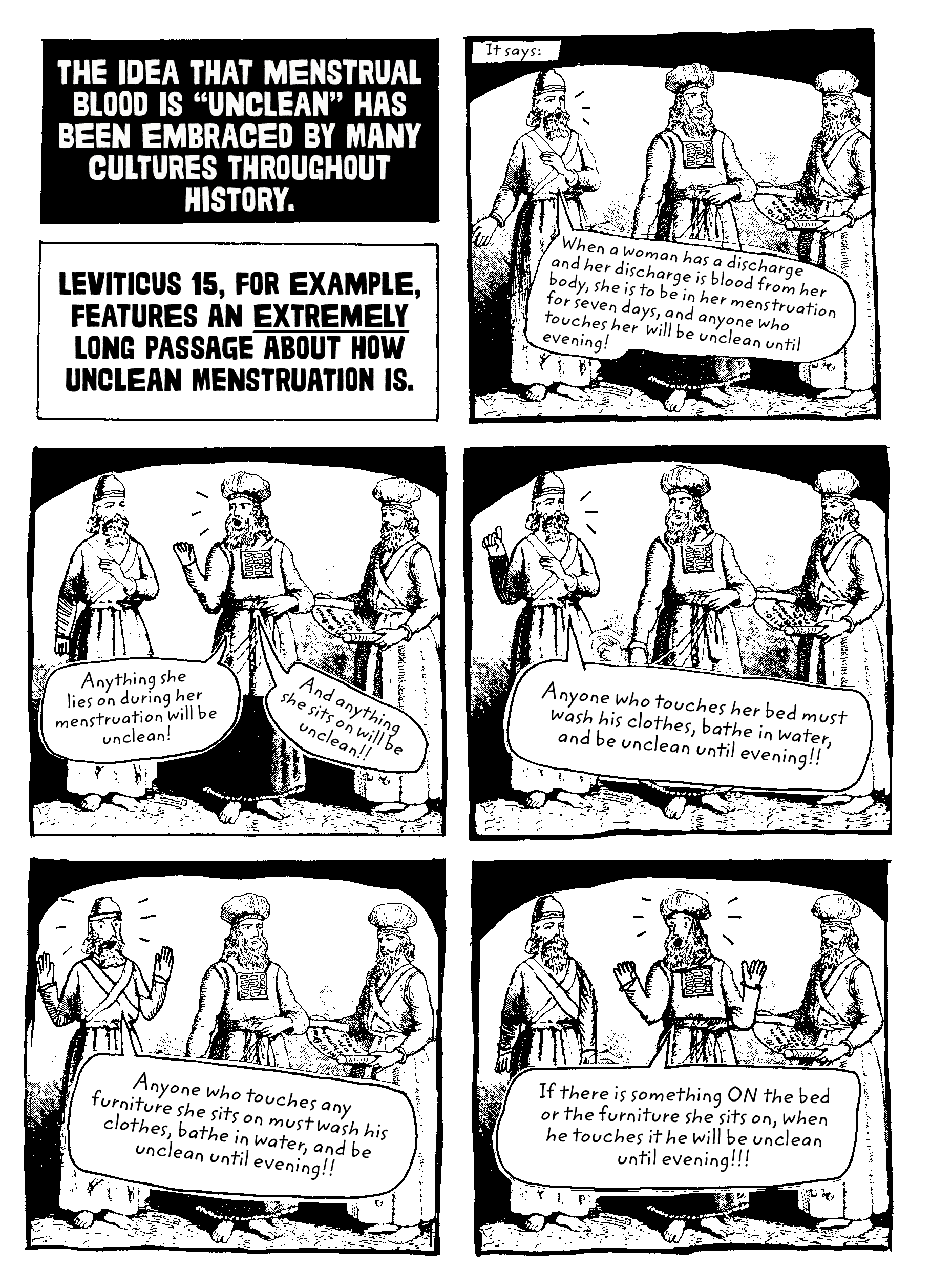

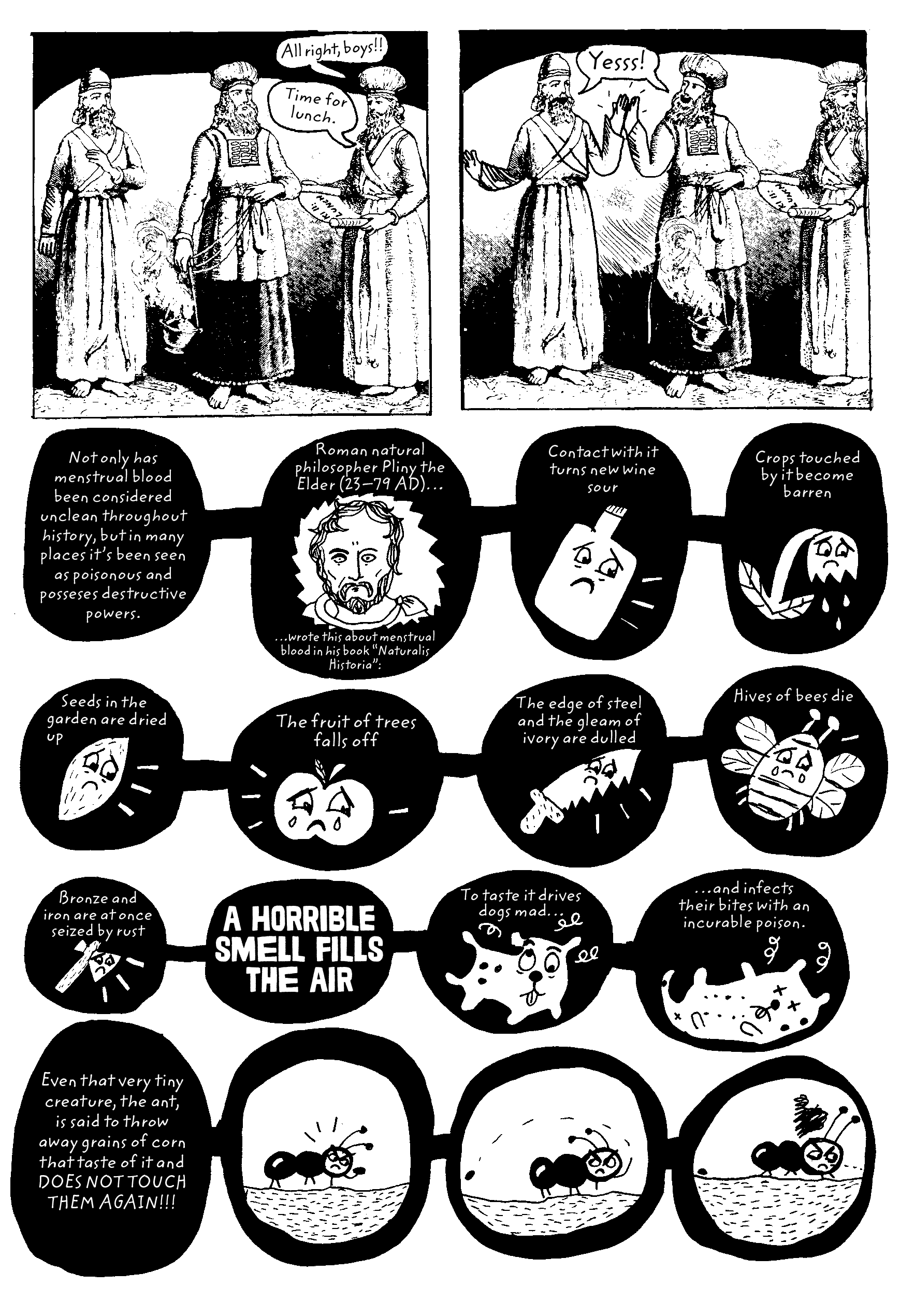

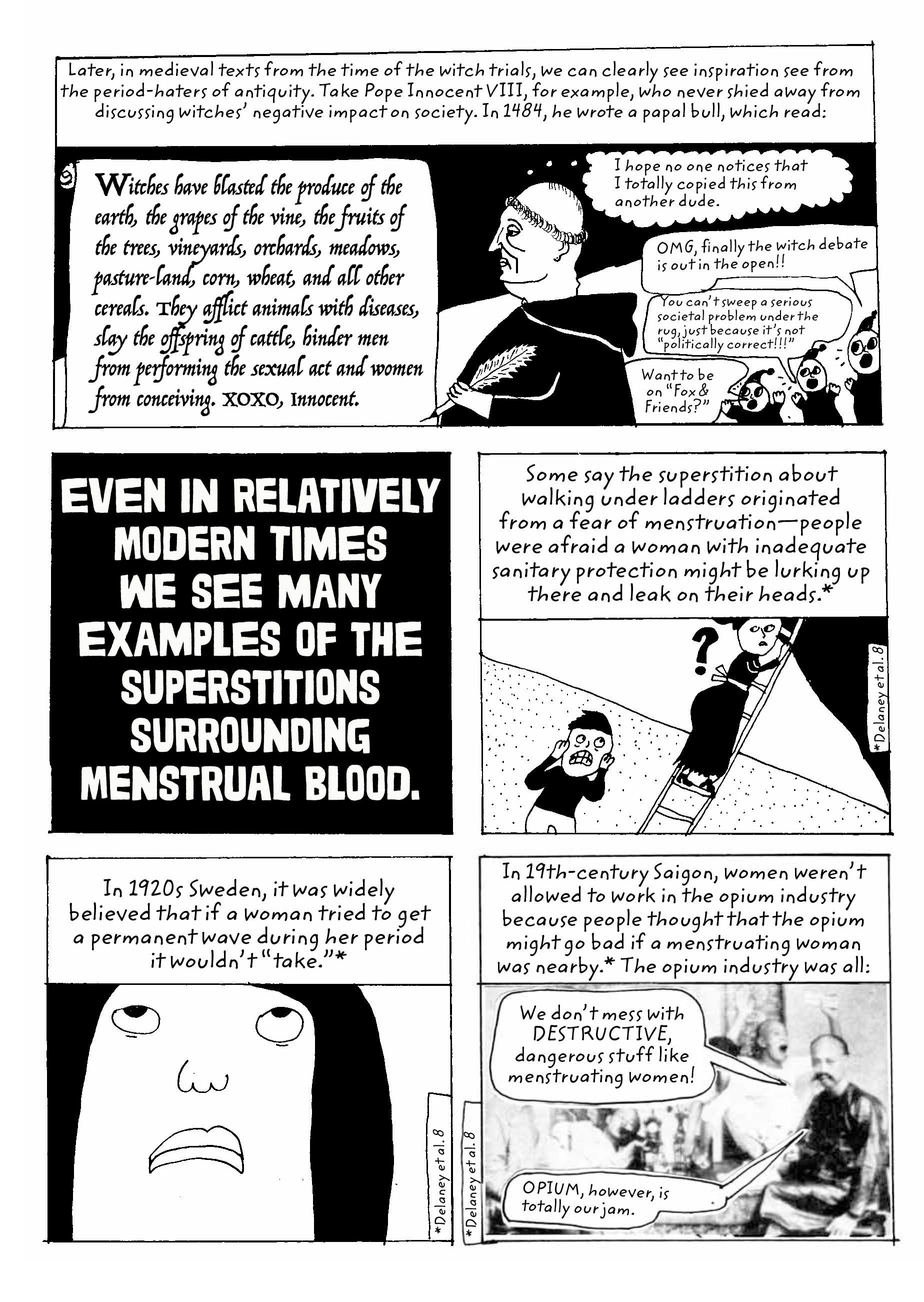

Fruit of Knowledge certainly achieves that artistic intention, turning a gallery of “Men Who Have Been Too Interested in the Female Genitalia” into an informative yet humorous hall of shame, and, in “Blood Mountain,” poking fun at the superstitions around menstruation, while also digging into ancient times, when it “appears that menstruation was MORE holy and LESS icky.”

For thousands of years and across cultures, Strömquist relays, the vulva and menstruation had been integral parts of the sacred landscape—vulvas made their appearance in Greek myth, Egyptian lore, European fables, and notably, monasteries, churches, and village gates in Celtic culture. It was once believed that the female orgasm was necessary (and thus highly valued) for procreation. Sounds a bit different than the way we treat the female body today, doesn’t it?

Strömquist explains the disparity this way: “The very overt hatred and fixation that the monotheistic religions have with the female body and sexuality [arose because religions]—in their early stage—were in competition with fertility cults.”

During the Enlightenment, and with the rise of medical science (and male doctors), those in power had to come up with new theories for female inferiority.

For thousands of years and across cultures, Strömquist relays, the vulva and menstruation had been integral parts of the sacred landscape. Click To TweetStrömquist continued explaining that:

“Science had to try to find explanations as to why women were different from men and couldn’t have the same access to power and money in society. Before they could say, ‘Women have no power in society because that’s what god wants’—but later they had to come up with scientific reasons. That’s when medical science started to obsess on things like the uterus, menstruation and so on.

“In the debate over if women could enter university in the end of the 1800s, there was a doctor who wrote a book that argued that women couldn’t enter university because of their menstruation. If they studied, their brain would use the blood they needed for menstruation, and become infertile. So if women started to study in the university, it would be the end of the human race.”

This might sound extreme to us now, but considering the contemporary struggle to simply close the gender pay gap or support working mothers—how far have we really come? Society continues to use the female body—and its natural functions—against women.

While much of what Strömquist covers in her work relates to the biologically female body, she also fixes her searing gaze on the binary two-gender system, criticizing the surgeries that intersex babies undergo, often in the first weeks of their life, which only serve to “categorize genitals” and “remove sensitive tissues that the person might miss later in life.”

In “Blood Mountain,” the chapter which covers menstruation, Strömquist explores the fallacy of PMS being linked to a particular gender, illustrating her point with a male figure skater lifting a leg to expose bloody panties, accompanied by the captioned thought that if we didn’t live in a binary two-gender society, “I could have drawn the first page of this chapter like this → Or in some completely different way!! Which I am too socially conditioned to even think of!!!”

Social conditioning plays a strong role throughout Strömquist’s work, and she’s keen to exploit that awareness, not allowing how we culturally perceive biology and gender to dominate her art.

In all areas of her work, Strömquist explores “provocative” subject matter. Last year, her art came under fire last year when Stockholm’s metro commuters found her subway illustrations of women menstruating “disgusting,” while others insisted it was awkward explaining the red stains to their children.

“There was a big debate over my pictures when they were displayed in the Stockholm Metro-station,” Strömquist says.

“They were vandalized twice so they had to be replaced with new prints. There was a political debate, where the populist right-wing party in Sweden wrote an article criticizing the use of tax money to support this kind of art and promised that if they got in power they would replace this kind of art with pre-modern oil painting. People still have quite strong feelings about [menstruation], which I find interesting.”

Despite the controversy over her artwork, she also “received a lot of support and positive reactions” for depicting menstruation—something that happens to millions of bodies every day—in a celebratory public forum.

Strömquist currently lives in Malmö, where she works for a youth radio station and hosts a political podcast. She has two new books in the works. One, a comic titled “Rise and Fall,” covers “climate change and problems of world capitalism.” The other is “a book about the social construction of romantic love,” which she hopes to see published in English as well.

In her chapter, “Upside Down Rooster Comb,” where she quotes Sartre and The Latin Kings, Strömquist also cites psychologist Harriet Lerner, who has been writing about the consequences of mislabeling the vulva as the vagina for decades. Lerner “likens this misuse of language to ‘psychic genital mutilation.’”

Whereas the vagina is often described in terms of absence, “a ‘hole’ waiting to be filled with a cock,” the vulva is very rarely mentioned—in conversation, and even in biology textbooks.

We are literally discouraged from properly naming the vulva. “If we don’t have the words,” Stromquist says, “we cannot understand what the organ is or how it looks and works. Words are really important. In many languages there isn’t even a proper word for the [female] sexual organ—one that isn’t an insult.”

Imagine being encouraged to call your arm your hand, or being told your entire life that your toes are your leg. This kind of senseless mislabeling encourages confusion, avoidance, and embarrassment, all of which prevent many people from treating the vulva with the respect and veneration it deserves.

If we don’t have the words we cannot understand what the vulva is or how it looks and works. Click To TweetGiven the current political climate in the United States, Strömquist’s vibrant, excoriating work is more necessary than ever. Fruit of Knowledge is the kind of self-care Western culture needs—accessible, intelligent, and engaging renderings of culture and history—that provide the encouragement to help us finally name and reclaim the female body.