With little more than 20 students—comprised almost entirely of trans children and volunteering teachers—the Chilean school, Escuela Amaranta Gomez, aims to unite a society that is tearing itself apart.

The chairs in the classroom of the Escuela Amaranta Gomez are organized in a circle. The crowd of children takes a while to simmer down, their ages ranging from 7 to 16. Tall, thin, and beautiful, Miss Antonia Jorquera presides before them, wearing a crown and a sash. She waves to the girls, who look at her agape as if she was a Disney princess. Antonia talks about her childhood in the Chilean south, where there was little to no television. A time when she adored pink.

“Like me!” a girl answers.

Antonia laughs. “I’d also put on my mom’s high heels,” she continues.

“Did you do it in hiding?” another girl asks.

“I’d wear them daily! But secretly, otherwise my mom would berate me.”

“My mom lets me,” another girl brags.

“My mom would also let me,” another voice joins.

The side conversation goes on for a while—the classroom brims with the noise of the children. Teacher Romina intervenes: “Could somebody in the classroom define what is a ‘Miss’?”

“A beautiful woman, a diva!” answer some girls. “It appears in the video games, whenever I miss a shot,” jokes a boy.

“What could you say about being a Miss, Antonia?”

“To be a Miss means a lot of things,” she answers, ever smiling, waving her hand softly as she speaks. “It doesn’t have anything to do with beauty standards. It’s about socializing things that are not shown—it is to represent the people who live in hiding.”

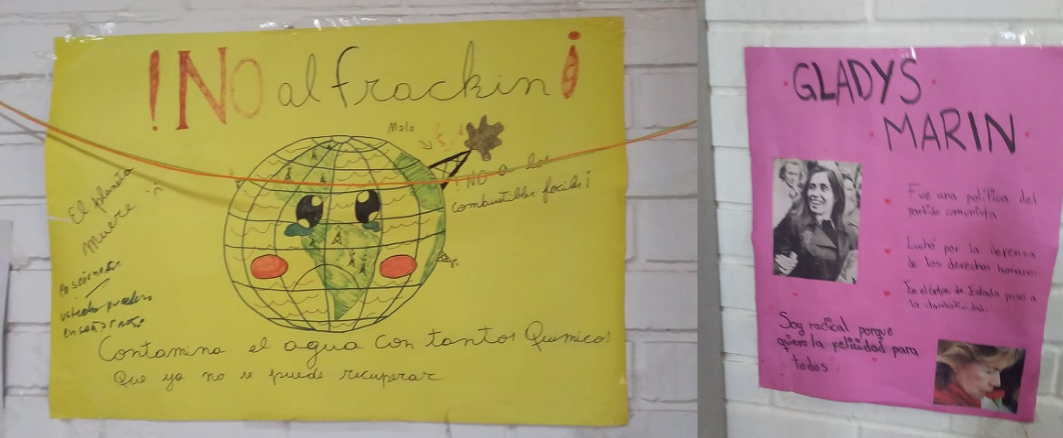

“No to fracking!” says a hand drawn poster on the wall. Below, a grieving Earth is filled with iron towers. “I’m radical because I want happiness for everybody,” quotes another. It shows legendary Communist politician and Pinochet critic Gladys Marín. In a corner, messages dangle from a string: “It doesn’t matter what you decide to do. Just make sure you’re happy”; “What’s broken can be forged once again”; “If it doesn’t hurt you, let live”;“It’s not a wrong body, it is mine, it belongs to me, it identifies me and I LOVE IT.”

To be a 'Miss' means a lot of things. It is to represent the people who live in hiding. Click To TweetJorquera is Miss Chile Trans, and minutes later will be joined by Fernanda Muñoz, Chile’s representative for Miss Trans Star International. They’re there to talk to the children as a part of their Civil Formation Workshop, one of the landmark classes in this trans feminist school. Profe Romina and most of the children here are transgender.

The school was created a little less than a year ago by Evelyn Silva and Ximena Maturana, both mothers of trans girls. It is a project of Silva’s Selenna Foundation, which protects the rights of transgender children in Chile. Wherever there’s a trans child, Selenna is there—usually using the school structures—offering speeches and workshops aimed at normalizing transgender and non-binary identities. (Just this past November, Chilean President President Sebastián Piñera signed a measure—the Gender Identity Law—which allows transgender youth over 14 to legally change their names, and guarantees their right to be officially addressed according to their true gender.)

“We have 50 families, more or less, with whom we work actively,” says Maturana. “This a communal work. It’s child, family and school. The foundation establishes strong bonds with whatever schools its children are in.”

Maturana says she didn’t realize the radical immersion she would undergo when she found herself fully committed to the cause. She began her journey by participating with her daughter—who is now a teenager—wherever and whenever she could, always following Silva’s lead. But eventually, she got asked to give talks by herself; she compares her change of worldview with her daughter’s transformation.

“I realized that my life before my daughter’s transition wasn’t going to be the same after,” she says. “I suddenly felt super involved with this social change—I realized that I could not only support my child, but also other children who needed it and whose parents didn’t have the time to do it.”

As a parent, Maturana recognizes the difficulty of accepting the reality that once your child begins to transition, their life in school could inevitably become more difficult before becoming better. There’s a lot of self convincing: It’s gonna be alright, they’re going to respect my kid.

“The thing is, children remember,” Maturana explained to me. “They’ve got enough consciousness to say, ‘you were previously this and now you’re that’. Then it’s the trans child’s turn to do the explaining. Over and over. And over again. It’s much easier when you start from scratch with your chosen name than having to struggle with an old version of yourself.”

Inevitably, violence kicks in.

While it manifests in all kinds of ways, Maturana says school violence often emerges through everyday actions, like when she used to pick up her daughter at school and every parent’s eyes were fixed on her as she came out. “‘I’m okay with you, but don’t mess with my child’, their eyes said. Before you realize it your kid ends up being the only one not invited to birthday parties. It’s sad that everybody’s in the birthday picture except for your child.”

Usually, before trans children officially enter any school, their parents speak with the headmaster in order to explain the need for the Foundation to preemptively address the students to raise awareness and respect through speeches.“The first thing the director often says is, ‘But the parents, they won’t understand’… I don’t believe any excuse to be valid, but there’s no one who knows parents better than the directors,” Maturana says.

Parents are—painfully—often the first to object to the speeches the Selenna Foundation gives. “Why should my child learn this stuff?” they complain. Maturana says she finds this rather ironic, considering that the Foundation has received calls from schools regarding “concerned” parents who’ve reported that their children are dating a trans classmate.

“I think parents can be even more screwed up than the kids,” Ximena posits.

The Misses’ visit became venting ground for both them and the children on their experiences in the school system. A trans girl of around ten years talked about the time a teacher shoved his foot into her path, tripping her onto the ground. Another trans girl remembers a series of violent bullying episodes. A gay friend of hers was beaten and bullied so much he hid in the bathroom and broke his finger punching the wall out of rage; she described a second episode where she lashed out and beat up a girl after being bullied herself.

Before you realize it your kid ends up being the only one not invited to birthday parties. It’s sad that everybody’s in the birthday picture except for your child. Click To TweetTeacher Romina intervenes quickly at the tail end of these recollections to remind the children that violence isn’t the answer, which was quickly objected to by another student. She felt it is only natural to lash out when you suffer from so much rage.

Romina knows something about pent up anger. A history teacher and trans activist, she put her pedagogy studies on hold for ten years in order to transit successfully. She finally got her degree two years ago, just after she got to change her name. Around the time of our conversation, she was going to retrieve her diploma with her new name as well.

Parents often recognize that their child can’t handle being in the same school they previously attended while they’re also in transition, so they take them out and let their children stay home. Some keep up by taking standardized tests, but others don’t even do that. “There’s a kid here [In the Amaranta Gómez School] who’s 16 and is about to enter fifth grade,” says Maturana. For years the child would constantly change schools, but only ever lasted a few months before giving up.

The Escuela Amaranta Gomez exists to put an end to that stigma, shame, and derailing of education. Classes start at 9 AM and end around 2:15 PM. Maturana arrives earlier because one of the girls arrives around 7:15, the only time her parents can drop her off. “The idea is to be as uncomplicated as possible so the parents can come drop off their kids. There can’t be any excuse for them not to come.”

With 22 children, the classes are divided in two, according to age. The day is divided in three modules and, according to the day they may have language, math, science, history or English. They also have workshops, which can range from art therapy and yoga, to programming and the aforementioned Civil Formation.

“The focus of the Civil Formation Workshop is more about participation rather than political alphabetization, like knowing about institutions, voting or traditional politics,” says Profe Pedro, a cis male history teacher for the teenage group. The Workshop is the only time all of the students are together. “It’s more focused on community participation, where the kids recognize themselves as political subjects in daily life and get to see school as a space for democracy.”

The Escuela Amaranta Gomez exists to put an end to the stigma, shame, and derailing of education that transphobia can cause. Click To TweetSuch a radical vision of school also means democratizing issues such as content. What do the kids want to learn? When I was interviewing Pedro, they were divided into groups of three tasked with drawing a comic on a different moment in colonial history.

Maturana discussed the merits of a roleplaying game the teens created:

“They made their own characters and through some chips and dice, they created a parallel world in which they travel through time. If you’re in a determinate space and time, in order to go further you have to get to know that place. So you have to learn if there’s a president, an emperor, what did they eat, how did they dress, if it was cold, whatever. They end up learning about science, history, human traits like empathy and responsibility, because your character also has qualities and defects.”

While trans children are the majority of the student population, the school’s not exclusive to them. It has also received cis children who have had problems with bullying or are sent by government support programs. The only requirement is for the parents to agree with the school’s priority: trans issues. Maturana talks about a cis boy who had suffered from a lot of bullying and had entered just three days ago: “His mom was telling me that yesterday afternoon he was feeling badly and that the only thing he wanted was to come here.”

There’s a reason it’s called Escuela, and not Colegio, two words often looked as synonyms in Spanish. If it’s Colegio, it means it has the approval of the Education Ministry. The approval of the Education Ministry means it fulfills certain requirements, which Silva and Maturana aren’t sure if they want to accomplish or abide by yet.

There’s no way a formal school would allow a child to enter just two weeks before closing the year. The Amaranta Gómez School does. The Education Ministry allows some flexibility in applying a different grading system rather than the traditional Chilean 1.0 to 7.0 (worst to best), but that’s not enough in this school. “It’s not like you’ve got to study for a test and that’s the all reflection of what you’ve learned,” says Maturana. “It doesn’t have to be a 7.0. It can simply be an accomplishment, a congratulations, and that’s something we don’t wanna lose.”

Profe Romina believes the Ministry’s focus doesn’t represent an adequate type of education. “It doesn’t give the teachers enough space to do the work we should really do, which is more oriented towards creation and not just obeying rules.”

Nevertheless, the Minister, Marcela Cubillos, actually came once and handed out a prize. “I forgot the name,” says Maturana, “but it was like ‘best relationship among the students.'” She still seems puzzled by the visit and no wonder, given that Cubillos is so conservative that when she was a Congresswoman, she voted against the legalization of divorce in 2004.

What’s most important about being recognized by the Ministry, however, is that the school receives financing by the State. As of this moment, all eight teachers are volunteers, and the children’s families don’t have to pay anything. Meanwhile, they’ve found financing through two international NGOs, one from the United States, and another from Switzerland. Now they’re going to apply to the International Trans Fund.

Such a radical vision of school also means democratizing issues such as content. What do the kids want to learn? Click To Tweet“What do you think about the people that criticize you because ‘that’s not how God made you’?” a boy asks Jorquera. “Actually, I’m a strong believer,” she answers. “Thanks to God I’ve achieved many things. I would say those people are wrong because he made us all according to his image.”

“When we went to the Civil Registry, there were a lot of religioses screaming at us,” remembers a girl, speaking of the bigoted protesters using their gender inclusive neutral form created by the trans community. As young as she is, she shows empathy even for those who are not willing to grant her the same.

Maturana doesn’t remember the episode in the Civil Registry, but she does remember a time they had a field trip to Congress. It was the first time protesters aimed their ire at the children. Religioses.

“That had never happened,” said Maturana, “and it was super uncomfortable, but the kids were very brave.” Usually it’s the parents who get all the bullets. They’re the degenerates, they’re the ones distorting the children. A news crew came along with the Minister during her visit, after which “a lot of people started writing on our page. Really nasty stuff.”

Luckily, there haven’t been any physical attacks, and Maturana believes the neighborhood has something to do with it. They feel safe there. Unlike other quarters in Santiago, this one boasts a hot history. The last bastion of social housing in Chile, the National Stadium nearby—created during the ‘60s—had served as a camp for torture and extermination during the days after the coup.

It was also there where, years later, a dozen freedom fighters in hiding were slaughtered by dictatorship soldiers. After the damages suffered during the 2010 earthquake, the neighborhood organized itself into an assembly that still exists today and offers services such as cleaning brigades, newsletters, recreational activities, and a mobile library.

For the moment, though, they’re still uneasy about posting their exact address.

Like so many places in the world, Chile finds itself in the crosshairs of two colliding forces. On one side, not only did our own Daniela Vega became the first trans person to present in the 2018 Academy Awards, but the film she starred in, A Fantastic Woman, won the Best Foreign Film Category. After a heavy debate, the Gender Identity Law was also approved, a process that until this legislation passed, could take years. (You can thank the 14 years limit to the concerned conservatives who, as always, issued their “think of the children” shields).

On the other hand, you’ll still find fascism. Pinochet fanboy, José Antonio Kast, lost his presidential run in 2017 with 7% of the votes and a unified base in the ultra right, among them evangelicals and neo nazis. A few months ago, the conservatives rallied against the “Gender Ideology”, a term they use to demonize anything related to gender equality, from feminism to trans rights. The gathering amassed thousands and featured quite a few gems: neo-nazi splinter groups going out of their way to beat up kids who were dancing to K-Pop, the police force—famous for gassing any kind of protest prowled the forefront stick in hand like guard dogs—and President Sebastian Piñera’s government defended the conservative demonstrators’ “freedom of speech.”

The jury’s still out on how long this hate-wave is going to last, but Romina is sincere with the teenagers. Given the life she’s had, her insight is useful, especially taking into account that at some point, they’re going to apply to colleges and jobs. “I believe they should learn to defend themselves. Not to make them rioters, but to make them aware that there is violence outside—it would be an irresponsibility not to convey that knowledge.”

Regarding the smaller children, Romina offers another strategy. “Personally, I just try to allow them to live their childhood. I don’t talk politics, gender or anything. As kids, they’re worried about the next Disney film, about Christmas, about screaming, playing and jumping.”

That’s Maturana’s strategy as well: “What they need the most is a mother’s complicity.”

As the Civil Formation Workshop was ending, and the younger children who had succumbed to uneasiness and had started slipping under the tables, sliding over the floor and playing, came back to their seats, Miss Fernanda provided some final words of advice: “What’s important is that we don’t put a shell on against the world.”