When we talk about gender, we often focus on topics specifically pertaining to feminism, like rape culture or discrimination against women. But gender norms affect everyone — and though they influence people’s lives in ways that are vastly different and of varying intensity, their impacts are ultimately connected in many ways, too.

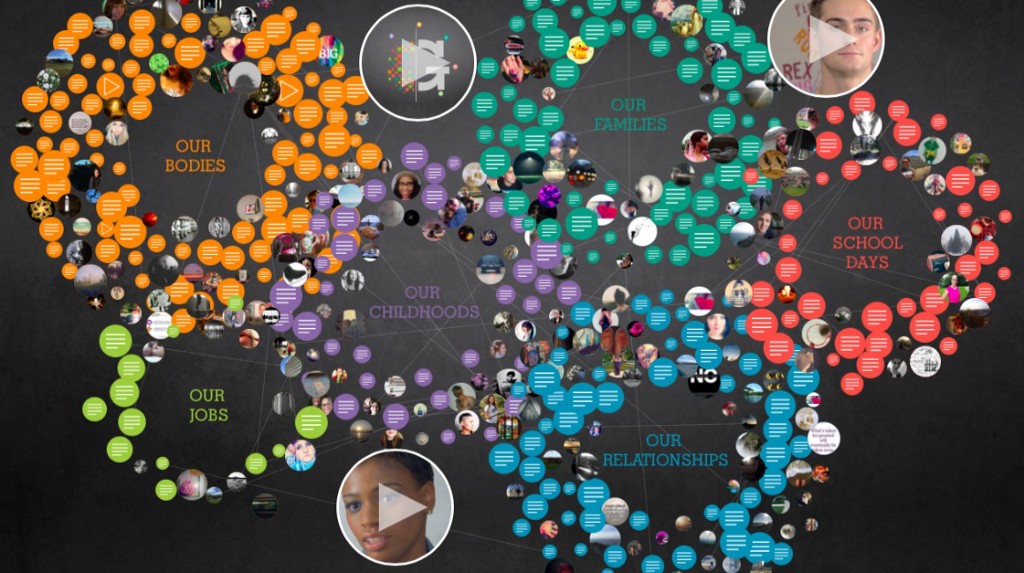

To explore the nuances of gender norms and identity, Breakthrough, a global human rights organization, has released an interactive multimedia project called The G Word. The project’s central conceit is simple: Ask people — men and women; straight, gay, and bi; cisgender and transgender — to share their experiences with gender norms. Stories gathered explore topics including how families react to stepping outside gender norms, workplace discrimination, and the power of childhood experiences.

The G Word shares videos, photos, and sometimes just text from users from all over the U.S. The project’s digital producer and filmmaker, Ishita Srivastava, has focused on bringing awareness to immigrant rights, especially for female immigrants, and was in charge of Breakthrough’s Restore Fairness campaign, which worked on immigrants’ human rights issues. Her documentary, Desigirls!, is about two queer Indian women in New York City who are grappling with issues of identity around their sexuality, gender, and immigrant culture.

The Establishment chatted with Ishita about her work on the project.

Casey Quinlan: Why did you think it was necessary to have a conversation about the ways in which gender norms and gender expression influence everyone’s lives, instead of separate conversations about how, say, rape culture affects lesbian and bisexual women, or how toxic masculinity affects the coming-out process for gay and bi men?

Ishita Srivastava: Research shows that gender norms . . . inform gender-based discrimination and violence. Instead of saying, “Here is the connection between the two,” we want to have people show it through their stories.

This is not just a women’s issue or LGBT issue; it’s everyone’s issue. Men grow up with these gender norms about masculinity, and they don’t even think about it. They often don’t think they have a gender story. But if you dig deep, a lot of guys talk about, “Well you know, I was 8 years old and I was in elementary school and I remember feeling really ashamed that I couldn’t throw very well and I got bullied or teased for it, and there was this time my sister was painting her nails, and I said, ‘I want to paint my nails’ and I got yelled at.”

A trans person who is being discriminated against and who can’t use the restroom — that story is not the same as the experience that a straight woman has while walking to school every day or that a straight guy has of feeling pressured at his fraternity and feeling like he doesn’t fit in. So it was intentionally about showing the connections between all of our experiences.

Casey: When we have conversations about privilege, there is a tendency for some people to proceed with the conversation as if you either have all of the privilege or you have none of the privilege, instead of you have the privilege of having an affluent background but not of being white, for example. Do you think these complicated identities make it necessary to have one interconnected web, so you can see the ways gender norms affect everyone differently?

Ishita: Yeah, I work on gender, of course, and gender-based discrimination and violence, but no one walks around with just one piece of their identity. We walk around with multiple pieces of our identity. I grew up in India. I’m a woman. I’m straight, but I’ve slept with women and I am an immigrant. But sometimes my immigrant experience has a stronger role to play in what’s going on than my being a woman, and sometimes it has less of a role to play.

There’s no way [experiences with gender identity] are disconnected from our class background, our immigration status, our sexuality, how people perceive us, our height, our ability, and our health. This project was focused on gender, and that’s what we’re highlighting, but the great thing about storytelling is that stories allow intersectional issues and nuances to show up in a way that isn’t overwhelming, in a way that feels natural and organic. Storytelling can be empowering. It can be really difficult. It can be really exposing.

To your question about privilege, we all carry different types of privilege around, some more than others, obviously, because we live in a society that has certain broader inequalities.

Casey: How did you bring awareness of the project to people who would be interested in sharing such intimate stories with you? One woman discusses an abusive relationship and a man discusses his coming-out process as an athlete, for example.

Ishita: One of the things I’ve found in my work and storytelling over the years is that the way we get people to share stories is to give them a story. If you say, “Tell me a story about this,” people say, “Oh, I don’t know if I have one,” but if I say, “When I was 15, this is what happened to me,” they’ll say, “Me too,” or “My friend has a story like that.”

Casey: Was it difficult to find cisgender heterosexual men who were willing to talk about how gender norms and gender expression have influenced their lives, given the likelihood that they are probably not having these conversations on a regular basis?

Ishita: The majority of the stories we get, because that is the reality of the world, are from women — so we get sexual assault stories and rape stories, traumatic stories. But we’ve been really intentional about reaching out to men. [Sharing] stories about masculinity with men has been the best way to get them [to participate], because putting out a call on Facebook wouldn’t really work. One of the things we did in the beginning was we created a few videos we produced ourselves that modeled the sorts of stories we wanted. A young gay man, Rex, told a story about being this all-star athlete in college and feeling like he couldn’t come out as gay because he wouldn’t be taken seriously as an all-star athlete.

After we shared Rex’s video, we got a story from a young man called Justin, who is black, grew up in the South, and is gay. And he talked about being at summer camp and thinking, “Oh my god, how can I be a black man and be gay?” Because black men are supposed to be super masculine. It was great because of the dimension of race and what that added to his perception of himself.

It’s definitely harder [to find stories from men], because they don’t think of themselves as having stories. My favorite story from a young man — I don’t know if he identifies as gay or straight — is about how when he was young, his sisters and mom started knitting, and he got really into it and started knitting and loved it. He had been knitting a scarf, and one day his dad came home from work early and saw him knitting. And he was shouted at by his father and told he could never knit again. And he was really affected by this. He shared this story, and while it’s not of course super-traumatic in the sense of being sexually assaulted, it does have an effect on how he thinks about what he can and cannot do in the world. So we used that story and created a graphic and shared it, and it had a lot of responses.

Casey: What conversations do you think we should be having about gender that we’re not yet having? Do you think we’re ignoring certain groups of people in particular when we talk about gender identities and gender expression?

Ishita: My favorite-ever piece [from The Establishment] was about street harassment and to be honest, I hadn’t really thought about how disability intersects with gender. It was a personal story about a woman being in a wheelchair, and it was about what her relationship to sexual harassment was. For example, I think for me and my team, when we saw that story, we said, “Oh, we need to focus on disability and mental health as well, and the connections between disability and how we present and how we get treated.” I think that’s one thing that is completely missing in the conversation. We shared that [story] and had a story from someone who had Asperger’s. She’s on the autism spectrum, and she was sexually assaulted and treated badly by partners, and then had a feeling like she deserved it. It was about her journey toward understanding that even though she had this mental disability, she deserved to be treated like a human being by her partners.

And of course, male survivors of sexual violence is another piece. We’ve gotten some stories definitely, but men feel like they can’t share their stories because they’re men and they aren’t supposed to get sexually assaulted. They think people won’t believe them and that they’ll be blamed for [the violence]. It’s a little tricky because there are men’s rights activists who claim that men get assaulted as much as women, which is like totally untrue, so we didn’t want to cater to them. But at the same time, we wanted to give [male survivors of sexual assault] a space.

The sexual assault campus movement has gotten pretty loud, and there are a lot of survivors leading that movement, which is amazing. I think the one thing is that we need to make sure women of color and people of color have a space to speak in that main narrative, because those voices sometimes get left out of the conversation. And those voices feel even less comfortable sharing their stories. A lot of young black women we’ve spoken to have told us that they are told it’s their fault that that they’re hypersexualized in this way. And there are people who are undocumented and not American citizens.

Casey: What’s next for the project?

Ishita: We’ve done a lot of outreach in the U.S., but what I’m working on right now is making it more accessible to a global audience, so to the language piece, I’m translating it and doing some data visualization around a world map. We’re partnering with organizations in different countries, highlighting different issues. We’re actually working on the next phase of our campus catalyst work, and there will be a multimedia project that The G Word will be a a part of. I’m working on multimedia that will support people who want to become catalysts on issues of gender violence on campus.