The way languages incorporate gender can have a powerful impact on the expression of identity.

Over the last few years, we’ve progressed significantly in our acceptance of gender fluidity: One seminal 2015 poll found that half of millennials in the United States believe gender isn’t limited to male and female, a meaningful change from previous generations. Today, Facebook offers a custom field for people to express their gender identity, and Tinder and OkCupid have expanded gender options that people can select before swiping left or sending a DM.

Wrapped up in this revolution is an understanding that conventional gender pronouns are extremely limited. But what if you spoke a language that didn’t even have separate words for “him” or “her”? Or what if just about every noun in your world was masculine or feminine — seemingly at random? What impact would this have?

It turns out, the way language is constructed can have a significant impact on the way people think and interact with the world. One rather chilling study, for instance, found that people who read in gendered languages responded with higher levels of sexism to a questionnaire they took after the study.

For those who don’t identify along the gender binary, these distinctions also matter. To find out how and why, I spoke with people from several countries who have come out as genderqueer, nonbinary, or gender-questioning. Their insights reveal the crucial, and often overlooked, importance of one’s native language in the expression of gender identity.

Before diving in to the intersection of language and gender identity, it’s important to understand some details. Broadly speaking, there are three ways gender can be incorporated into language:

*Natural gender languages, including English and Swedish, don’t typically categorize non-human, non-animal nouns into male or female categories. A table and tree are it, while people are he or she.

*In gendered languages like Spanish, German, and French, both people and objects are given a gender. A table, for instance, is a feminine noun in French — “She is a lovely table!” — while a tree is a masculine noun in German. “I planted him in the forest, where he will grow very tall!”

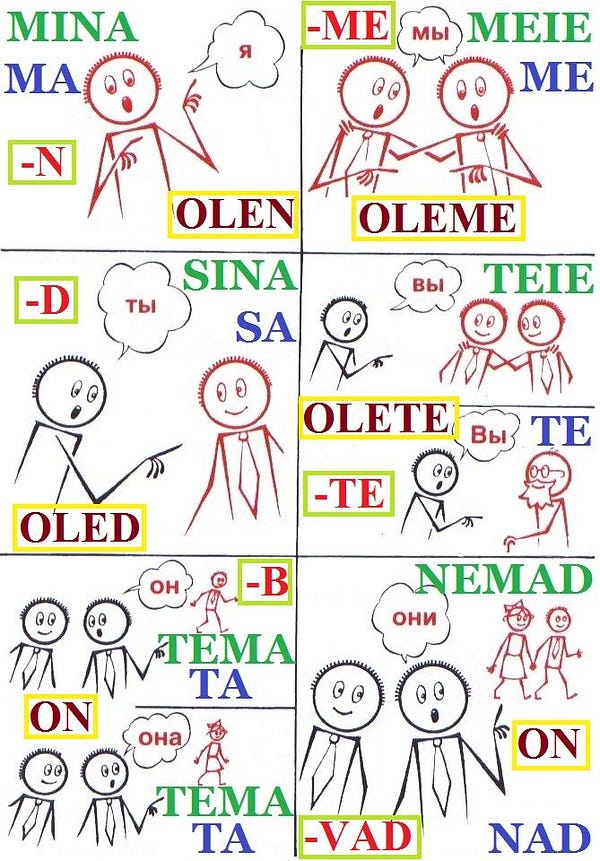

*Chinese, Estonian, and Finnish are examples of genderless languages, which don’t categorize any nouns as feminine or masculine, and use the same word for he or she in regards to humans.

Half of millennials in the United States believe gender isn’t limited to male and female. Click To Tweet“Natural gender” languages like English perpetuate the idea of a strict gender binary for humans. But there is one option to challenge these parameters: the use of gender-neutral terms. In English, these terms include they as a singular, ze/zir or zie/zir, ze/hir or other variations, and Mx. in written forms.

These terms are undoubtedly beneficial, helping to allow for expression across the gender spectrum. But are they enough?

In a 2016 survey — Bucking the Linguistic Binary — 20% of monolingual, transgender English speakers said, “yes, English gender-neutral language allows me to express my identity”; 31% said “no, it does not allow for adequate identity expression”; and 19% said “yes and no.” About 4% specified that they felt that it currently did not allow them to express their identities, but, “the situation was improving and that they were hopeful that time and advocacy would lead to increased acceptance of the language that would allow them to express their identities.”

Those who answered “yes and no” detailed both positive and negative aspects. One participant wrote:

“When I was using gender-neutral pronouns in English, it was almost impossible to get anyone who wasn’t in the queer community to use ‘they’ for me consistently. This was at an early stage of me asking them not to use ‘she’ (the pronoun I was ‘assigned’ at birth), so I think people were still getting used to the idea of any pronoun other than ‘she’ for me. But I had the impression that people outside the queer world (not LGBT but ‘queer’ as in challenging gender binaries) had an even harder time with the idea of a gender-neutral pronoun than with the idea of someone ‘crossing’ gender lines (i.e. requesting ‘he’ instead of ‘she’). So people would default to ‘she’, which was unbearable to me. So ‘he’ felt lots safer to me since it was farther away from ‘they’ and easier for people to wrap their minds around.”

If it seems like English-speakers are dissatisfied, the situation for speakers of gendered languages is worse. In the same survey, transgender French respondent #171 was clear and succinct:

“[S]peaking a gendered language as an agender person fuckin’ sucks. I’m constantly misgendered, or I’m misgendering myself in order to be understood.”

Misgendering in a gendered language was explained by another respondent:

“For example, in English, there are multiple nouns that I can use to classify myself (partner, student) without making reference to gender, whereas in German I’m supposed to say the feminine form of many common categories into which I fit, like student (Studentin), and have to explain myself when I refuse.”

In English, one can say they are a teacher with a partner, and no one’s gender is revealed; French and German lack that luxury.

Transgender German respondent #98 added:

“The options that English presents work reasonably well for me and I can express my gender identity and use preferred pronouns […]. [In] German I struggle a lot with language and [I am] often very unhappy with the situation of [the lack of] German gender-neutral language. I lack usable and easy to learn/apply pronouns and descriptions of myself. That the language is very gendered is a big problem in my life.”

Russian is a gendered language that does feature a neuter third-person pronoun, оно [it]. This pronoun is not typically applied to people — instead it is used only for objects with neuter noun names, typically borrowed words like кафе (cafe) that do not take a masculine or feminine case. A few gender pioneers, however, have co-opted it. For example, Seroe Fioletovoe [Grey Violet] — a transgender Russian activist who is part of the artist collective Война [War], best known for spawning punk activists Pussy Riot — uses “оно” to describe themself.

‘That the language is very gendered is a big problem in my life.’ Click To TweetPolina Ravlyuk, a Russian blogger who runs an information portal on gender and gender identification, wrote to me in an email:

“We don’t have a gender-neutral pronoun [for people]…Agender people use feminine or masculine pronouns according to their personal preference. There can also be situations where a woman can refer to herself in the masculine way grammatically and vice versa. It’s worth noting that the issue isn’t widely discussed [yet] in Russia, because in my opinion society isn’t ready to accept gender on a spectrum. ‘Homosexual propaganda’ is still a fineable offence in the Russian Federation…”

Tosha, a young Russian who identifies as agender, told me:

“I use masculine pronouns, even though they don’t suit me very well. Plural or ‘neuter’ cases in Russian aren’t comfortable for me. Maybe someday I could use them, though. I also speak English, and I use the ‘they/them’ in English. Because of the language barrier, that doesn’t feel unnatural for me, and besides, [i]n Russian almost all the verbs and adjectives have gender, and in English it’s not like that. Pronouns in English don’t hurt me, as long as no one does it on purpose.

In my opinion, the language plays a pretty large role in how agender people feel about themselves, because [Russian] isn’t flexible enough for us. It doesn’t allow for a lack of gender; you always have to pick something. It shapes how we are thought about and sometimes contributes to social dysphoria. In my own family, it’s been difficult for most of them, though my friends, mother, and grandmother easily adjusted to using masculine pronouns to refer to me. Those who don’t know why I use that case either question it, or they think I think I’m a guy, or they just ignore it.”

Tosha also notes that there’s the option to use a plural pronoun when referring to agender people. “When I don’t know someone’s gender, I talk about them in the plural,” they say. “I think after some time I’ll be able to do the same for myself [in Russian].”

It’s clear that, not surprisingly, natural gender and gendered languages pose problems for identity expression. But what about genderless languages? Are these, then, the gold standard?

A young Estonian agender person interviewed for this article who prefers the name Paul does find “tema,” the genderless Estonian pronoun, helpful. Temais used only for humans, and when used in a sentence, it is neither masculine nor feminine. Paul writes:

“Usually people use the gender-neutral ‘tema’ [when] talking about any person, and because it’s the most common way to refer to a person, there is no issue with which pronoun to use. I prefer ‘they’ or ‘he’ in English, but I don’t usually say it to people unless they ask. That is because I am not really out as non-binary. In Estonian there is no gender in pronouns, but there are marker words like ‘tüdruk’ (girl), ‘preili’ (Ms.), or ‘neiu’ (a young woman) that I don’t identify with, but which are used by older people addressing me. I would prefer the gender-neutral pronoun ‘tema’ or my name.

Friends and close acquaintances call me ‘Paul,’ which I really like to be called. I somehow identify more with neutral or masculine marker words, and names. In English when I use ‘they’ to refer to a person, most people don’t notice it. But that’s maybe because the people I talk to in English are not native speakers. So there is some slip of pronouns going on unintentionally, especially with Estonian people speaking in English. We don’t have gendered pronouns, so a regular person might call a cis man a she by accident, and not be corrected, because we are not native speakers.”

Asexual Finnish student Kati agrees, saying, “I’m so happy Finnish has only one [ungendered] pronoun. It makes some things so much easier…one does not need to make assumptions about gender when trying to address someone.”

Having just one pronoun for humans doesn’t equal perfect equality in society, though. Turns out that genderless languages can include “seemingly gender-neutral terms” that do in fact have a sneaky male bias, just like natural and gendered languages. For example, the word lakimies (literally lawman or lawyer) in Finnish is what is called a false generic. In principle, it refers to all lawyers, but in practice, it refers only to male lawyers. Female lawyers are called just that: female lawyers. Men are the standard and everything else is the exception.

What can we take away from all this? Agender people have the hardest time expressing their identity in highly gendered languages, but genderless languages are not the utopia one may imagine. Assumptions about the binary nature of gender and the status of masculinity seem to survive intact, even under genderless language conditions. Though Estonian people using the term tema may not specifically picture a man or a woman, they invariably picture either a man or a woman, not anyone else in between.

In Gender Outlaws: The Next Generation, authors Kate Bornstein and S. Bear Bergman emphasize the politics of language itself and of having “the agency to have our own words and definitions of them, and insist upon them to linguistic passers-by.” A natural gender language with a history of borrowed words, like English, has the flexibility to create pronouns to suit a person.

This is far from perfect — but it may be the best option yet for those who identify along a spectrum.